DREAMS FOR A NEGLECTED RIVER

© Torben Jenk, 2007.

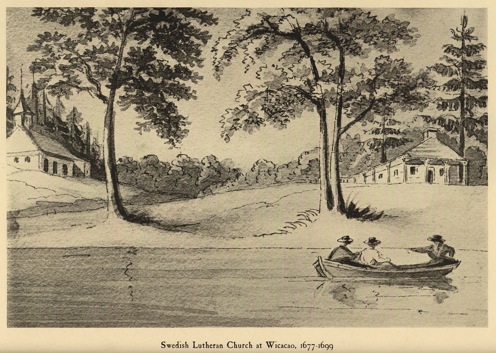

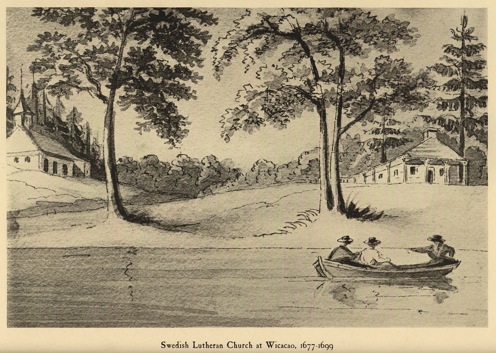

Few pre-industrial sites remain along the Delaware River. South of Christian Street is the charming Gloria Dei (Old Swedes') church, built between 1698 and 1702, replacing the log church of 1677. Resting in the graveyard among carved green slate tombstones are "Nells Laickman who died Dec. 4, 1721, aged 55," "Mary, the wife of Andrew Robeson who died Nov. 12, 1716, aged 50 years" and Peter and Andreas, the infant sons of the minister Andreas Sandel who died in 1708 and 1711.

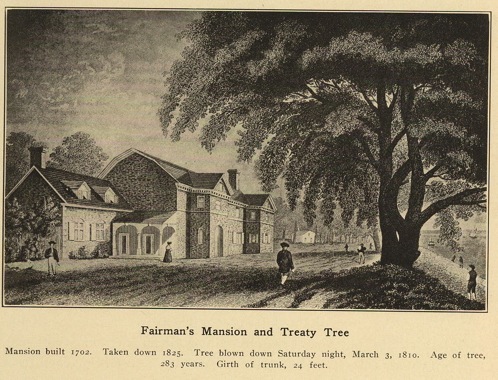

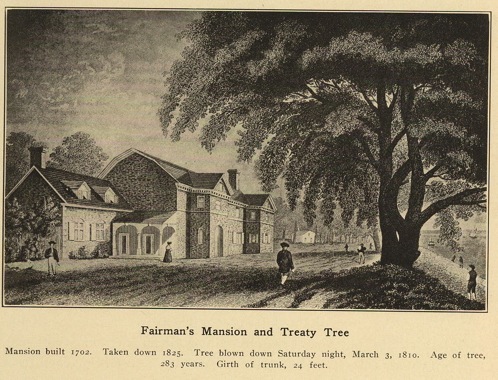

At Penn Treaty Park, near Columbia Avenue, numerous historic markers commemorate the Great Treaty of Amity between William Penn and the Lenape in 1682. The current park sits atop 19th century ship yards, reclaimed in the 20th century by concerned neighbors for recreational use. From this location, the Delaware River swings northeast, offering the most beautiful view of Philadelphia, celebrated in the iconic masterpieces of Benjamin West, Thomas Birch, and Edward Hicks. Sought after by William Penn for his country home, this land had already been settled and held a house built by Elizabeth Kinsey and Thomas Fairman.

Industry gobbled up most of the twenty-two mile waterfront on the Delaware within Philadelphia city limits. In the 1960s, Ian McHarg—the renowned landscape architect, planner, teacher, writer, and lecturer—gathered information for his program entitled "Dream for a Neglected River."

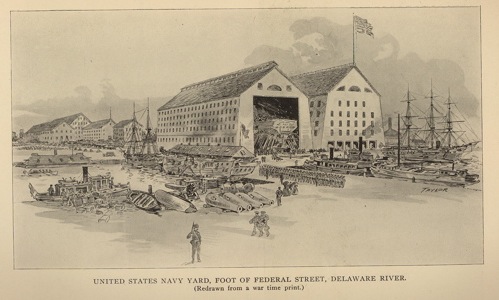

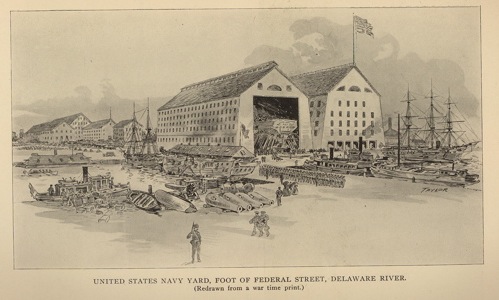

Once there had been a hundred and sixty finger piers. Old prints showed boats moored, some at dock, others moving in the bustling channel. No more—there were only three working piers in the entire length we surveyed. The remaining piers and pierhead buildings were in profound disrepair. It was clear that they had no future. Moreover, the attitude of the city toward its waterfront could not have been more cynical; it was home to a municipal incinerator, two thermal electric plants, a police academy, Graterford Prison, and the one appropriate installation, the Torresdale Treatment Plant. These facilities occupied only a trivial amount of available space, the rest was in various conditions of abandonment and deterioration. Still, it was easy to see what the Delaware waterfront had once been. Just across the Neshaminy Creek lay Andalusia, the beautiful Biddle property, with riverfront beaches, bluffs, marginal wetland vegetation, and woodlands. Moreover the view across the river to New Jersey was quite attractive…. Water quality in the Delaware was abysmal. A gauging station located under the Ben Franklin Bridge for decades had never shown any dissolved oxygen. The surfeit of Philadelphia sewage was consuming it all. It was not until after President Lyndon Johnson's 209 program for increased sewage treatment that oxygen appeared, and almost immediately so did the shad run. And now in the 1990s the sturgeon are returning. The land use history was dominated by shipping, piers, warehouses, ship handlers, and associated industry, which included major shipbuilding facilities that survived through WWII.

McHarg and his students realized "a major opportunity for a connected facility throughout the length of the river lay in that area between the bulkhead and the pierhead. The bulkhead was the land edge, the pierhead was the limit that piers could occupy. Let us propose filling between bulkhead and pierhead to create a continuous new edge, from 300 to 600 feet wide. We would use this as the lever to create humane and viable prospective land uses. This wide ribbon could connect to the riverfront and give structure to the many abandoned and vacant sites." Lady Bird Johnson was long a supporter of McHarg's approach to "Design with Nature." President Johnson promised support for McHarg's plan for the Delaware if McHarg could get the support of Philadelphia's leaders, but, McHarg told me, "that pestilential man Ed Bacon wanted all the Federal resources going to fulfill his plans for Center City." Indeed Bacon, the Executive Director the Philadelphia City Planning Commission from 1949 to 1970, wanted to concentrate on restoring the colonial charm of Society Hill for residents and on building new offices around Penn Center. Some say Bacon tried to "cauterize" Center City by proposing the Vine Street Expressway and the Callowhill Industrial District (around one thousand buildings were demolished) and the South Street Expressway (opposed by residents and never built). The building of Interstate 95 further cut off Philadelphians from the Delaware River, offering travelers along this mostly elevated roadway a view across wreck and ruin.

Since McHarg's proposal, dozens if not hundreds, of dreams for the Delaware have been proposed by professional planners, neighbors and various advocacy groups—most sit unread and forgotten, some resurface with gaudy illustrations. Five years ago the Philadelphia Inquirer sponsored a series of "visioning sessions" for Penn's Landing, hoping to revitalize that moribund space—nothing happened. Grumbling continues from old timers made cynical after decades of false promises and the history-averse gentrifiers with utopian visions.

Ultimately, development is driven by private investment and that has been scarce and uninspired. One of the few new residential developments under construction is "Waterside Square," just north of Spring Garden Street, a ten-acre "gated community"—frustrating those who want public-access to the river front. Designed by WRT (the successor firm to Wallace, McHarg, Roberts and Todd), Waterside Square lacks the public-access and recreational uses that McHarg planned and others implemented so masterfully along the Hudson River in NYC.

Politics and corruption have also stalled progress. Governor Rendell has halted all building beyond the bulkhead line, looking to mandate public access to the waterfront while also assessing increased leases for the riparian rights. An official of the current Philadelphia administration was recently convicted for soliciting "pay to play" campaign contributions from developers for Penn's Landing; other officials are under indictment and investigation. Pennsylvania politicians searching for revenues "without raising taxes," legalized the casinos with "license fees." Four sites along the Delaware have been proposed for casinos: "Foxwoods" between Tasker and Reed streets, north of the Home Depot and Wal-Mart); "Riverwalk" at the former City Incinerator at Spring Garden; "SugarHouse" at the former site Jack Frost Sugar site at Shackamaxon Street; and "Pinnacle" at the former Cramp Shipyard (north of Susquehanna Avenue). Foxwoods and SugarHouse were selected in the first round in December 2006. Community opposition to the proposed casinos has spurred a new series of plans.

What follows is a description of the river, past and present, between Spring Garden Street and Cottman Avenue, including the waterfront sections of Kensington, Fishtown, Port Richmond, Bridesburg, Frankford and Tacony. Private developers have collectively published plans for over 5,000 new residences along the river, most being sited on the demolished industrial sites.

Because building beyond the bulkhead line has been blocked, developers are proposing forty- to sixty-story residential towers west of Delaware Avenue near Poplar Street. Much of the current low-rise, low-use warehousing will disappear, now owned mainly by speculators. Just north of Penn Treaty Park is the monumental cast concrete Delaware Generating Station, used only during periods of peak demand. The Cramp Machine and Turret House (west side of Richmond Street below Girard Avenue) is soon to be demolished for construction of new ramps to I-95. On the riverside is the WWII "graving dock," which was filled in years ago. This site was praised as one of the best for a casino and will likely be considered for such a use during the second round of gaming licenses. Much of the hundreds of acres of riverside land up to Allegheny Avenue was built by the Philadelphia and Reading Rail Road as their Port Richmond Coal Wharves, now controlled and used by the road builders, James J. Anderson Construction. Look carefully and you will see sorted mountains of asphalt, gravel, broken concrete, brick, and even toilets.

Where Interstate 95 meets Allegheny Avenue once stood the enormous Riverdale Glue Works, run by Benjamin Webb in the 1890s. Where Allegheny meets the Delaware is what might be called a "pinky pier," a tiny park atop a slender pier, which commemorates General Pulaski, a beloved hero of the many Polish residents of Port Richmond. Immediately to the south are four loading ramps for rail cars, which were transported by floats over the Delaware five at a time to New Jersey. North, beyond the Parking Authority Impound Lot and auction site, is the huge Tioga Marine Terminal, used by freighters and barges to deliver goods and gases, as they had in the 1890s. Just beyond the Richmond Generating Station and the Betsy Ross Bridge, Delaware Avenue meanders and dies at the "Quick Way [garbage] Transfer Station." In 1890 it was the site of Remmey Refractory, where "over 14,000 fire bricks per day are turned out, and 30 skilled workmen employed." Between Orthodox and Buckius is the cleared sixty-seven-acre parcel known as "Philadelphia Coke" (1927-1982), now proposed for "720 units [residences] and 70,000 square feet of retail space and recreational areas."

In Bridesburg, Seller and Jenks streets are named after early machine builders William Sellers and Alfred Jenks (no buildings seem to survive). Farther north, near Pratt Street, is "Keystone Refining Co." (c.1920); tugs still deliver barges just a few hundred feet away. At Bridge Street, Ellis Coffee roasts, as it has in Philadelphia since 1854. Nothing seems to survive of Robert Foerderer's "Glazed Kid Mfy." The site is now occupied by Rohm & Haas, which in addition seems to have swallowed the "Tacony Chemical Works."

Crossing the Frankford Creek, Sunoco Chemicals is to the southwest, the Frankford Arsenal to the northeast. Nothing seems to survive of the "Philadelphia Cordage Works" of Edwin Fitler, where great ropes were wound. Just north of the Frankford Arsenal is the "Frankford Arsenal Access Area." A four-and-a-half-acre riverside park is proposed adjacent to the Lardner's Point Water Pumping Station. The eighteen-acre site of Dodge Steel / Tacony Iron Works is supposed to be converted to residential use. Much of the Disston complex survives and no plans to use the site have been published, but the campus-like assemblage of two-story buildings offers a sensitive developer the chance to create unique homes within the old walls, an improvement over the vinyl- and stucco-clad townhouses being promoted elsewhere—McHarg called them "ticky-tacky houses."

Below Princeton Avenue is the thirteen-acre site of the "Tacony Army Warehouse," cleaned up by the Federal government for $10 million then sold at auction for $2.5 million. The developer now promotes "Tacony Pointe. Luxury 2 & 3 Bedroom Townhomes with garages on the Delaware River." A dozen years ago, a sliver of public land was set aside along the river just south of Princeton Avenue for the "Tacony Boat Launch" and the gravel beach is a popular fishing site. Just to the north of Princeton Avenue is the private Quaker City Yacht Club, established in 1887. They pay a mere dollar a year to lease the ground from the adjacent St. Vincent's Orphan Asylum. As the Archdiocesan budget bleeds, the developers circle like sharks. Farther north at the "Northern Shipping" site (7777 State Road) is the largest planned development: 1,546 new residential units.

Planners hope to extend Delaware Avenue to prevent the dead end at the transfer station, and want to revitalize the ten-mile riverside rail route to the Lardner's Point Pumping Station for "The Kensington & Tacony Trail and Delaware River Heritage Trail / Delaware River Greenway"—a dreadful name but hopefully a sign of collaboration. The trail should extend through Pennypack Park, Pleasant Hill Park, and up past Foerderer's gorgeous "Glen Foerd" mansion before crossing the Poquessing Creek into Bucks County. By incorporating this trail into the route of the East Coast Greenway, Philadelphia will become accessible to those cycling between Calais, Maine, and Key West, Florida (21 percent of the 3,000 mile East Coast Greenway route is in place).

Planners also have proposed placing thirty-six signs that feature "Riverside Plants," "American Sycamore," "Double-Crested Cormorant," "Striped Bass," "Disston & Sons," Lardner's Point" and "The Delaware River." More picturesque than informative, the subjects rarely consume three sentences. Proud civic groups have printed more informative guides. Scholars will wade through the environmental lawsuits filed among current and former businesses, their insurance companies and the government agencies for the most accurate description and effects of the industrial development and uses along the Delaware River.

It took over forty years to extend the Schuylkill River Trail from the Art Museum to Locust Street. Philadelphians have enthusiastically embraced that recently-completed two mile extension, giving hope to those who dream of a twenty-two mile trail along the Delaware River.

RESOURCES

Information on Ian McHarg is taken from his book "A Quest for Life—an Autobiography" (Wiley, New York, 1996), pp. 346-347, and from conversations on June 16, 1999. McHarg's thoughts on how to accommodate man-made structures within the existing natural order are best described in "Design with Nature" (first published by Natural History Press, Philadelphia, 1969).

Various "official" plans for the Delaware River exist, including those by the Delaware River City Corp., the Office of Housing and Community Development, Field Operations ["North Delaware Riverfront, Philadelphia—A Long-Term Vision for Renewal and Redevelopment"], and Penn Praxis ["Plan Philly"]. A more personal vision is by architect and long time riverside resident Al Johnson, "BOBS—Boulevard of Boats and Ships" (Alley Friends Architects, 2002).

Bruce Stutz, "Natural Lives,

Modern Times" by Bruce Stutz (Crown, 1992) is

perhaps the best book published on the natural and

cultural history of the Delaware River from Cape May

to the headwaters in New York. Stutz includes

stories of many animals, including shad, snapping

turtles, sturgeon, and muskrat, showing a fondness

for the human characters who hunt them. There are

other interesting on the Philadelphia neighborhoods

of Fishtown and Tacony on pages 147-202. Highly

recommended.

Bruce Stutz, "Natural Lives,

Modern Times" by Bruce Stutz (Crown, 1992) is

perhaps the best book published on the natural and

cultural history of the Delaware River from Cape May

to the headwaters in New York. Stutz includes

stories of many animals, including shad, snapping

turtles, sturgeon, and muskrat, showing a fondness

for the human characters who hunt them. There are

other interesting on the Philadelphia neighborhoods

of Fishtown and Tacony on pages 147-202. Highly

recommended.

John Frederick Lewis, "The Redemption of the Lower Schuylkill—the river as it was, the river as it is, the river as it should be" (City Parks Association, 1924). A well-illustrated and passionate plea for "There is no reason why the Schuylkill below the Dam should not be as beautiful and useful as it is above it, and there is no reason why the Dam, which is a purely artificial construction, should act as a curse to bar further improvement to the naturally beautiful river which flows for miles so close to our doors."

© Torben Jenk, 2007.

Few pre-industrial sites remain along the Delaware River. South of Christian Street is the charming Gloria Dei (Old Swedes') church, built between 1698 and 1702, replacing the log church of 1677. Resting in the graveyard among carved green slate tombstones are "Nells Laickman who died Dec. 4, 1721, aged 55," "Mary, the wife of Andrew Robeson who died Nov. 12, 1716, aged 50 years" and Peter and Andreas, the infant sons of the minister Andreas Sandel who died in 1708 and 1711.

At Penn Treaty Park, near Columbia Avenue, numerous historic markers commemorate the Great Treaty of Amity between William Penn and the Lenape in 1682. The current park sits atop 19th century ship yards, reclaimed in the 20th century by concerned neighbors for recreational use. From this location, the Delaware River swings northeast, offering the most beautiful view of Philadelphia, celebrated in the iconic masterpieces of Benjamin West, Thomas Birch, and Edward Hicks. Sought after by William Penn for his country home, this land had already been settled and held a house built by Elizabeth Kinsey and Thomas Fairman.

Industry gobbled up most of the twenty-two mile waterfront on the Delaware within Philadelphia city limits. In the 1960s, Ian McHarg—the renowned landscape architect, planner, teacher, writer, and lecturer—gathered information for his program entitled "Dream for a Neglected River."

Once there had been a hundred and sixty finger piers. Old prints showed boats moored, some at dock, others moving in the bustling channel. No more—there were only three working piers in the entire length we surveyed. The remaining piers and pierhead buildings were in profound disrepair. It was clear that they had no future. Moreover, the attitude of the city toward its waterfront could not have been more cynical; it was home to a municipal incinerator, two thermal electric plants, a police academy, Graterford Prison, and the one appropriate installation, the Torresdale Treatment Plant. These facilities occupied only a trivial amount of available space, the rest was in various conditions of abandonment and deterioration. Still, it was easy to see what the Delaware waterfront had once been. Just across the Neshaminy Creek lay Andalusia, the beautiful Biddle property, with riverfront beaches, bluffs, marginal wetland vegetation, and woodlands. Moreover the view across the river to New Jersey was quite attractive…. Water quality in the Delaware was abysmal. A gauging station located under the Ben Franklin Bridge for decades had never shown any dissolved oxygen. The surfeit of Philadelphia sewage was consuming it all. It was not until after President Lyndon Johnson's 209 program for increased sewage treatment that oxygen appeared, and almost immediately so did the shad run. And now in the 1990s the sturgeon are returning. The land use history was dominated by shipping, piers, warehouses, ship handlers, and associated industry, which included major shipbuilding facilities that survived through WWII.

McHarg and his students realized "a major opportunity for a connected facility throughout the length of the river lay in that area between the bulkhead and the pierhead. The bulkhead was the land edge, the pierhead was the limit that piers could occupy. Let us propose filling between bulkhead and pierhead to create a continuous new edge, from 300 to 600 feet wide. We would use this as the lever to create humane and viable prospective land uses. This wide ribbon could connect to the riverfront and give structure to the many abandoned and vacant sites." Lady Bird Johnson was long a supporter of McHarg's approach to "Design with Nature." President Johnson promised support for McHarg's plan for the Delaware if McHarg could get the support of Philadelphia's leaders, but, McHarg told me, "that pestilential man Ed Bacon wanted all the Federal resources going to fulfill his plans for Center City." Indeed Bacon, the Executive Director the Philadelphia City Planning Commission from 1949 to 1970, wanted to concentrate on restoring the colonial charm of Society Hill for residents and on building new offices around Penn Center. Some say Bacon tried to "cauterize" Center City by proposing the Vine Street Expressway and the Callowhill Industrial District (around one thousand buildings were demolished) and the South Street Expressway (opposed by residents and never built). The building of Interstate 95 further cut off Philadelphians from the Delaware River, offering travelers along this mostly elevated roadway a view across wreck and ruin.

Since McHarg's proposal, dozens if not hundreds, of dreams for the Delaware have been proposed by professional planners, neighbors and various advocacy groups—most sit unread and forgotten, some resurface with gaudy illustrations. Five years ago the Philadelphia Inquirer sponsored a series of "visioning sessions" for Penn's Landing, hoping to revitalize that moribund space—nothing happened. Grumbling continues from old timers made cynical after decades of false promises and the history-averse gentrifiers with utopian visions.

Ultimately, development is driven by private investment and that has been scarce and uninspired. One of the few new residential developments under construction is "Waterside Square," just north of Spring Garden Street, a ten-acre "gated community"—frustrating those who want public-access to the river front. Designed by WRT (the successor firm to Wallace, McHarg, Roberts and Todd), Waterside Square lacks the public-access and recreational uses that McHarg planned and others implemented so masterfully along the Hudson River in NYC.

Politics and corruption have also stalled progress. Governor Rendell has halted all building beyond the bulkhead line, looking to mandate public access to the waterfront while also assessing increased leases for the riparian rights. An official of the current Philadelphia administration was recently convicted for soliciting "pay to play" campaign contributions from developers for Penn's Landing; other officials are under indictment and investigation. Pennsylvania politicians searching for revenues "without raising taxes," legalized the casinos with "license fees." Four sites along the Delaware have been proposed for casinos: "Foxwoods" between Tasker and Reed streets, north of the Home Depot and Wal-Mart); "Riverwalk" at the former City Incinerator at Spring Garden; "SugarHouse" at the former site Jack Frost Sugar site at Shackamaxon Street; and "Pinnacle" at the former Cramp Shipyard (north of Susquehanna Avenue). Foxwoods and SugarHouse were selected in the first round in December 2006. Community opposition to the proposed casinos has spurred a new series of plans.

What follows is a description of the river, past and present, between Spring Garden Street and Cottman Avenue, including the waterfront sections of Kensington, Fishtown, Port Richmond, Bridesburg, Frankford and Tacony. Private developers have collectively published plans for over 5,000 new residences along the river, most being sited on the demolished industrial sites.

Because building beyond the bulkhead line has been blocked, developers are proposing forty- to sixty-story residential towers west of Delaware Avenue near Poplar Street. Much of the current low-rise, low-use warehousing will disappear, now owned mainly by speculators. Just north of Penn Treaty Park is the monumental cast concrete Delaware Generating Station, used only during periods of peak demand. The Cramp Machine and Turret House (west side of Richmond Street below Girard Avenue) is soon to be demolished for construction of new ramps to I-95. On the riverside is the WWII "graving dock," which was filled in years ago. This site was praised as one of the best for a casino and will likely be considered for such a use during the second round of gaming licenses. Much of the hundreds of acres of riverside land up to Allegheny Avenue was built by the Philadelphia and Reading Rail Road as their Port Richmond Coal Wharves, now controlled and used by the road builders, James J. Anderson Construction. Look carefully and you will see sorted mountains of asphalt, gravel, broken concrete, brick, and even toilets.

Where Interstate 95 meets Allegheny Avenue once stood the enormous Riverdale Glue Works, run by Benjamin Webb in the 1890s. Where Allegheny meets the Delaware is what might be called a "pinky pier," a tiny park atop a slender pier, which commemorates General Pulaski, a beloved hero of the many Polish residents of Port Richmond. Immediately to the south are four loading ramps for rail cars, which were transported by floats over the Delaware five at a time to New Jersey. North, beyond the Parking Authority Impound Lot and auction site, is the huge Tioga Marine Terminal, used by freighters and barges to deliver goods and gases, as they had in the 1890s. Just beyond the Richmond Generating Station and the Betsy Ross Bridge, Delaware Avenue meanders and dies at the "Quick Way [garbage] Transfer Station." In 1890 it was the site of Remmey Refractory, where "over 14,000 fire bricks per day are turned out, and 30 skilled workmen employed." Between Orthodox and Buckius is the cleared sixty-seven-acre parcel known as "Philadelphia Coke" (1927-1982), now proposed for "720 units [residences] and 70,000 square feet of retail space and recreational areas."

In Bridesburg, Seller and Jenks streets are named after early machine builders William Sellers and Alfred Jenks (no buildings seem to survive). Farther north, near Pratt Street, is "Keystone Refining Co." (c.1920); tugs still deliver barges just a few hundred feet away. At Bridge Street, Ellis Coffee roasts, as it has in Philadelphia since 1854. Nothing seems to survive of Robert Foerderer's "Glazed Kid Mfy." The site is now occupied by Rohm & Haas, which in addition seems to have swallowed the "Tacony Chemical Works."

Crossing the Frankford Creek, Sunoco Chemicals is to the southwest, the Frankford Arsenal to the northeast. Nothing seems to survive of the "Philadelphia Cordage Works" of Edwin Fitler, where great ropes were wound. Just north of the Frankford Arsenal is the "Frankford Arsenal Access Area." A four-and-a-half-acre riverside park is proposed adjacent to the Lardner's Point Water Pumping Station. The eighteen-acre site of Dodge Steel / Tacony Iron Works is supposed to be converted to residential use. Much of the Disston complex survives and no plans to use the site have been published, but the campus-like assemblage of two-story buildings offers a sensitive developer the chance to create unique homes within the old walls, an improvement over the vinyl- and stucco-clad townhouses being promoted elsewhere—McHarg called them "ticky-tacky houses."

Below Princeton Avenue is the thirteen-acre site of the "Tacony Army Warehouse," cleaned up by the Federal government for $10 million then sold at auction for $2.5 million. The developer now promotes "Tacony Pointe. Luxury 2 & 3 Bedroom Townhomes with garages on the Delaware River." A dozen years ago, a sliver of public land was set aside along the river just south of Princeton Avenue for the "Tacony Boat Launch" and the gravel beach is a popular fishing site. Just to the north of Princeton Avenue is the private Quaker City Yacht Club, established in 1887. They pay a mere dollar a year to lease the ground from the adjacent St. Vincent's Orphan Asylum. As the Archdiocesan budget bleeds, the developers circle like sharks. Farther north at the "Northern Shipping" site (7777 State Road) is the largest planned development: 1,546 new residential units.

Planners hope to extend Delaware Avenue to prevent the dead end at the transfer station, and want to revitalize the ten-mile riverside rail route to the Lardner's Point Pumping Station for "The Kensington & Tacony Trail and Delaware River Heritage Trail / Delaware River Greenway"—a dreadful name but hopefully a sign of collaboration. The trail should extend through Pennypack Park, Pleasant Hill Park, and up past Foerderer's gorgeous "Glen Foerd" mansion before crossing the Poquessing Creek into Bucks County. By incorporating this trail into the route of the East Coast Greenway, Philadelphia will become accessible to those cycling between Calais, Maine, and Key West, Florida (21 percent of the 3,000 mile East Coast Greenway route is in place).

Planners also have proposed placing thirty-six signs that feature "Riverside Plants," "American Sycamore," "Double-Crested Cormorant," "Striped Bass," "Disston & Sons," Lardner's Point" and "The Delaware River." More picturesque than informative, the subjects rarely consume three sentences. Proud civic groups have printed more informative guides. Scholars will wade through the environmental lawsuits filed among current and former businesses, their insurance companies and the government agencies for the most accurate description and effects of the industrial development and uses along the Delaware River.

It took over forty years to extend the Schuylkill River Trail from the Art Museum to Locust Street. Philadelphians have enthusiastically embraced that recently-completed two mile extension, giving hope to those who dream of a twenty-two mile trail along the Delaware River.

RESOURCES

Information on Ian McHarg is taken from his book "A Quest for Life—an Autobiography" (Wiley, New York, 1996), pp. 346-347, and from conversations on June 16, 1999. McHarg's thoughts on how to accommodate man-made structures within the existing natural order are best described in "Design with Nature" (first published by Natural History Press, Philadelphia, 1969).

Various "official" plans for the Delaware River exist, including those by the Delaware River City Corp., the Office of Housing and Community Development, Field Operations ["North Delaware Riverfront, Philadelphia—A Long-Term Vision for Renewal and Redevelopment"], and Penn Praxis ["Plan Philly"]. A more personal vision is by architect and long time riverside resident Al Johnson, "BOBS—Boulevard of Boats and Ships" (Alley Friends Architects, 2002).

Bruce Stutz, "Natural Lives,

Modern Times" by Bruce Stutz (Crown, 1992) is

perhaps the best book published on the natural and

cultural history of the Delaware River from Cape May

to the headwaters in New York. Stutz includes

stories of many animals, including shad, snapping

turtles, sturgeon, and muskrat, showing a fondness

for the human characters who hunt them. There are

other interesting on the Philadelphia neighborhoods

of Fishtown and Tacony on pages 147-202. Highly

recommended.

Bruce Stutz, "Natural Lives,

Modern Times" by Bruce Stutz (Crown, 1992) is

perhaps the best book published on the natural and

cultural history of the Delaware River from Cape May

to the headwaters in New York. Stutz includes

stories of many animals, including shad, snapping

turtles, sturgeon, and muskrat, showing a fondness

for the human characters who hunt them. There are

other interesting on the Philadelphia neighborhoods

of Fishtown and Tacony on pages 147-202. Highly

recommended.

John Frederick Lewis, "The Redemption of the Lower Schuylkill—the river as it was, the river as it is, the river as it should be" (City Parks Association, 1924). A well-illustrated and passionate plea for "There is no reason why the Schuylkill below the Dam should not be as beautiful and useful as it is above it, and there is no reason why the Dam, which is a purely artificial construction, should act as a curse to bar further improvement to the naturally beautiful river which flows for miles so close to our doors."