© Philadelphia Year Book, 1917.

Disston and Sons, Keystone Saw Works, 1872-

6700-6800 State Road & 5100-5200 Unruh Street, Philadelphia PA 19135

(between Unruh Street and Princeton Avenue, east of State Road to the Delaware River)

© Harry C. Silcox, Ed.D.,

Workshop of the World (Oliver Evans Press,

1990).

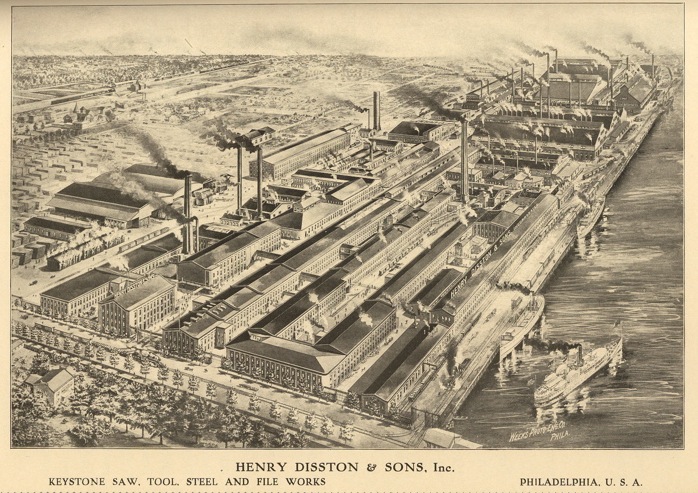

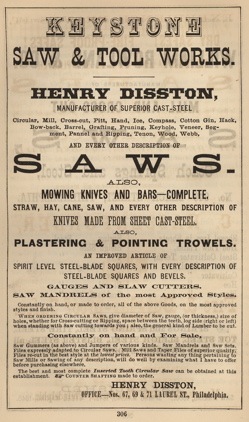

At its zenith, Henry Disston

and Sons employed an average of 2,500 workers, covered

sixty-four acres, and comprised sixty-four buildings.

Until its sale to H.K. Porter in 1955, it was a

family-run firm. It had sales branches in nine cities,

including Tokyo, and a plant in Canada. The largest saw

manufacturer in the world, Disston and Sons also produced

files, tools of all types, springs, and steel plate, as

well as special steel jobs. The company's Keystone

trademark on a product indicated high-quality to all who

knew the reputation of the firm. 1

Saws remained Disston's best known product throughout its

existence; indeed every imaginable sort of blade for

cutting wood or metal was produced at the saw works. The

process of creating a handsaw blade involved eighty-two

steps. It began with the making of steel in crucible pots

which were poured into molds that produced ingots. The

ingots originally were flattened by screw-type vices;

later steam pressured hammers were used. The process of

flattening continued in the rolling mills, where large

sections of rolled steel plate were routinely turned into

saw plate steel. After teeth were cut in the steel "in

the soft," the metal was tempered in a precision furnace

before hardening in a bath, it was then heated again in a

tempering oven and allowed to cool naturally. Tempering

gave the steel elasticity (spring) and durability. The

next step was "smithing,"—hand-hammering the blade

to perfect flatness and subjecting it to several stages

of grinding and filing. The trademark then was etched on

the blade and the teeth were set by angling every other

tooth to the left or the right. Thus, when the saw was in

use, the teeth cut a channel slightly larger than the

width of the blade, which prevented the blade from

binding in the channel.

Disston produced wooden saw handles and the brass screws

with which they were attached to the blades. This process

involved eighteen steps. Handles were made from applewood

logs, which were first cut to the proper thickness and

then aged in the open air for three years. The applewood

was then "ripped" cut, marked to pattern, sawed inside

and outside, oiled, nose-fonned, sanded, varnished,

carved, polished, bored, and split. Finishing the handles

was one of the few jobs that women performed in the

Disston works, (the company employed 195 women and 2,605

men in 1916). 2

During its peak years ofproduction, Disston used some

35,000 files per year to sharpen saws. Thus, file-making

machines and mechanical sharpening machines were

important components of the Disston plant. Files, like

saws, demanded the best hard steel available. The steel

ingots for the files received a slightly different

treatment in the rolling mills than those used to produce

saws. The file ingots were reheated and rolled into large

bars. These bars were cut into pieces, which in turn were

rolled into bars of decreased diameter and increased

length until they formed the size of file required. Once

the desired thickness and widths were reached, the strip

of steel traveled to the file works where it was cut into

proper lengths. The file blank was then "tanged," the

tang being the smooth, pointed end on a file which is

usually fitted with a handle, although frequently it

could be employed without a handle. This was done by

heating one end of the file and forging a tang from it.

The worker in this operation was seated before an

automatic hammer with a small furnace close at hand. The

temperature in the file oven was crucial to this

operation, as too much heat would prevent the file from

being properly teethed and too little heat would not

allow the workman to successfully mold the tang.

The files were put into air-tight boxes and placed in

annealing ovens, which were set to a predetermined

temperature. Once removed from the oven, the files cooled

in the boxes, not in the open air. These processes caused

the file to warp, or become uneven, so that it then had

to be taken to the straightening department, and thence

to the grinding department where the files were made

perfectly smooth so that teeth could be cut evenly into

them. The teeth were then cut into the soft metal with a

chisel-like machine, and a final heating hardened the

file. In all, Disston produced 50 types of files, some

flat, some rounded, and with variable teeth that ranged

from the rasp file to a fine file for aluminum.

3

The Disston plant site is divided by Knorr Street into

two main components. North of the Knorr Street gate on

New State Road are the steel and power plants, and the

rolling mills, to the south are the offices and

production buildings. The steel plant consists of an

armor-plate building, a steel-fumace building, and

rolling mills. The armor-plate building had large dies

that stamped out plates of steel for tanks in World War

II. Making steel required raw iron and steel scraps which

were stored in a large yard located next to the steel

furnace building. The crucible pot method was used to

melt the ore and scraps to form ingots. Adjacent to the

steel-fumace building were the rolling mills, where the

steel ingots were rolled into sheets of steel. The stack

on the power plant, which dominated the Tacony landscape

for years, was destroyed by an explosion in 1951 when

workmen did not properly blow out the gas fumes from the

stack before igniting the furnace. Except for the rolling

mills and the annor-plate building, these structures are

empty shells today.

The area south of Knorr Street is far more complicated to

describe, it contains a jumble of varied buildings, some

dating back to the 1872-1878 era. These include

grindstone sheds, a hardening shop, lumber yard, file

forge building, jobbing building, machine building, and

production buildings for hand saws, long saws, circular

saws and band saws. With the exception of the lumber yard

and the grindstone sheds most of these buildings are

still standing today.

A small part of the site south of Knorr Street remains

industrially active under ownership of Disston R.A.F.

Industries. This company produces large circular saws for

cutting hot steel. A small hardening shop, a torch-steel

cutting shop, and a teeth-cutting and smithing shop

function daily. More than twenty employees work under the

direction of Roland Woehr. However, this factory at New

State Road south of the Knorr Street gate is a shell of

the once mighty Disston and Sons Keystone Saw

Works. 4

1 Harry C. Silcox,

"Henry

Disston and Sons 1840-1955: The Rise and Fall of

America's mightiest Saw Works," unpublished manuscript,

(Philadelphia, 1989).

2 Philip Scranton and

Walter Licht, Work

Sights, Industrial Philadelphia, 1890-1950

, (Philadelphia,

1986), pp. 170-181.

3 "The

File, Its History and Making," The Disston Crucible: A

Magazine for the Millman, (January, February, March,

April, 1914), [available at the Free Library of

Philadelphia, Logan Square, Philadelphia].

4 Interview with Bob

Bachman and Roland Woehr at Disston and Sons site by

Harry C. Silcox, December 27, 1988.

Update May

2007 (by

Torben Jenk):

Many buildings remain, but most are in poor shape.

The buildings

along the north side of Unruh Street include decorative

cast iron "star bolts" (describing their common

shape)which are here shaped like keystones with the

letter 'D' within, a clear reference to Disston and the

Keystone Saw Works. Stacks of grinding stones are visible

where Unruh Street meets the Delaware River, some stuck

together with concrete and formerly used as a bulkhead.

Truck and auto repairs seem to be the only use today. It

appears that the buildings directly north of those along

Unruh have been demolished. Farther up State Road, at

#6795, is the entrance road to Disston Precision and the

rest of the former Disston complex. The wall along State

Road to the north is made of sandstone, possibly from

used grinding stones. On the south side you get the best

idea of the campus of two-story brick buildings. To the

left are 20th century buildings, tall single-story metal

structures, mostly vacant. Farther east along the

Delaware River is a finer collection of used grinding

stones.

Most impressive

is the steel furnace building with a date stone that

reads, '1940.' Only forty feet of the chimney remains

beside this robust building. Ovalized iron flues pierce

the roof-like glassless skylights, while the interior is

gutted and rotting.

Farther west is the rolling mill, identified by a date

stone that reads '1936', and shows a keystone and a

roller in relief. An auto scrap yard occupies the space

to the north.

Disston Precision

is still in operation and makes huge saw blades, valve

components, press plate, clutch components, shredder

knives and slitters. Disston offers the following

services: heat treating, flattening, grinding, laser

cutting, plasma burning, waterjet cutting, precision

machining and fabrication.

Other tenants include Marjam, which distributes building

materials; and American Lighting and Signalization, which

installs and maintains roadway lighting, traffic

signalization, airport lighting, street lighting,

interstate signing, and underground and overhead utility

lines.

There is talk of adapting the Disston complex for loft

apartments, and commercial and office space. Most of the

other industrial sites along the Delaware have or will be

demolished. The complex at Disston offers an opportunity

and challenge for a creative developer who wants to offer

something more enticing than the two-thousand vinyl-clad,

vanilla box townhouses being proposed just north and

south.

To the north of Disston, on the south side of Princeton

Street, was the Tacony Army Plating Plant, built in 1941

with the mission of making plates for tanks in WWII. The

200,000-square-foot building remained open through the

1970s and officially closed in 1983. At a cost of $10

million, the US Army Corps of Engineers demolished the

building in 2004. The site was sold at auction for $2.5

million and plans exist for 407 residences to be known as

"Tacony Pointe." A small park is along the Delaware River

with a public access Tacony Boat Launch. Just north of

Princeton Street, along the Delaware, is the Quaker City

Yacht Club, a private club for boating enthusiasts and

social members, established in 1887. It leases land from

the adjacent and still operating St. Vincent's Orphan

Asylum, which is shown on the 1895 Bromley Atlas (plate

48). The same plate shows the “American Wire Glass

Mfg. Co. of Frank Shuman.

Resources:

Harry C. Silcox, "A

Place To Live and Work, The Henry Disston Saw Works and

the Tacony Community of Philadelphia"

(Pennsylvania

State University Press, University Park, PA, 1994).

Hexamer General Survey #707-708 (1873)

"Henry Disston & Sons' Tacony

Works."

Hexamer General Survey #955 (1875) "Henry

Disston & Sons' Tacony

Works."

Hexamer General Survey #1266 (1878) "Henry

Disston & Sons' Tacony

Works."

Hexamer General Survey #1407 (1879) "Henry

Disston & Sons' Tacony

Works."

Hexamer General Survey #1763-1764 (1883)

"Henry Disston & Sons' Tacony

Works."

© Edwin T.

Freedley, Philadelphia

and its Manufactures (1867), p. 306.