Kensington

& Frankford—Textiles, Metals & Beer.

SIA tour June 8,

2007.

Tour leader: Torben Jenk

1215 Unity Street, former site of Quaker Felt.

Harry Lonsdale, Churchville Fabrics, weaving and textile finishing.

4355 Orchard Street, former site of “H. Riehl & Son,” Textile Machinery.

Paul Wagner, former owner of Riehl.

Matt & Ian Pappajohn, Pappajohn Woodworking, millwork & cabinetmakers.

Gregory August, August Interiors, conservator of Riehl patterns.

2439 Amber Street, former site of Weisbrod & Hess Brewery (1882-1938).

Tom Kehoe, Nancy & Bill Barton, owners and operators of Yards Brewing.

3450 J Street, former site of Luithlen Dye.

Jeb Wood, Ward Elicker Casting, sculpture foundry.

2050 Richmond Street, former Turret & Machine Shop of Cramp Shipbuilding Company.

Joel Assouline, Assouline & Ting, distributor of gourmet foods.

Kensington & Fishtown riverfront: Penn Treaty Park, former site of Neafie & Levy, misc. shipways and Cramp Graving Dock (filled in).

INTRODUCTION

Fearful of fire and filth, William Penn excluded industrial activities from his “Greene Countrie Towne” from the beginnings in 1681. But Penn had industrial interests, writing in 1701 “Get my two mills finished and make the most of these for my profit, but let not John Marsh put me to any great expense.” By 1708 Penn laments “Our mill proves the unhappiest thing of the kind, that ever man, I think, was engaged in. If ill luck can attend any place more than another it may claim a charter for it. I wish it were sold.” It was, in 1714, to Thomas Masters who, in 1715, received t he first patent issued to any person in the American Colonies “for the sole Use and Benefit of A New Invencon found out by Sybilla, his wife, for Cleaning and Curing the Indian Corn growing in the severall Colonies in America...” 1

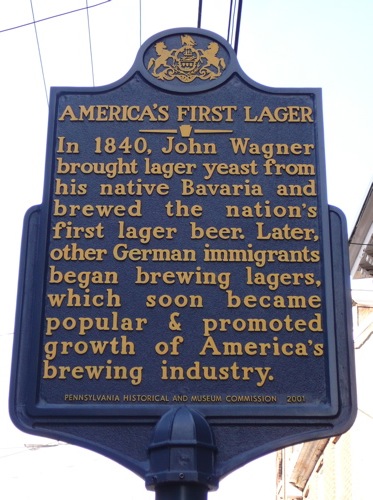

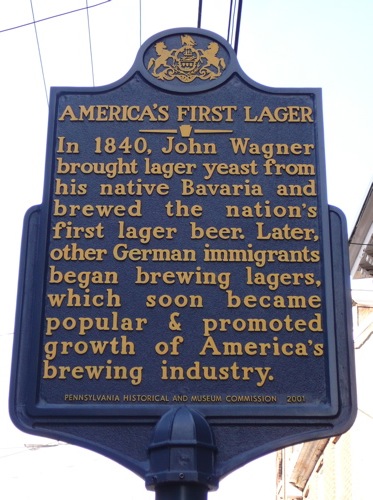

So began the industrial activity in the ancient neighborhoods of Northern Liberties, Kensington and Frankford. In 1787, John Fitch and his “superior Mechanical Genius” Henry Voight fashioned boilers and chains to propel the first steam boat. Improved foundry techniques allowed early locomotives to be built here in the 1830s, followed by Charles Cramp’s massive steam ships. Cheers to all that hard work, John Wagner brewed the first lager beer in America, behind his house, in 1840. Industrial activity across many of the twenty seven districts of Philadelphia County made this the largest center of machine building in 19th century America. Only upon consolidating these productive neighborhoods in 1854 could the City of Philadelphia claim its title as “Workshop of the World.”

On our tour we will learn about long lost enterprises, visit active manufacturers, meet generations of entrepreneurs and experience the rebirth of centuries-old industrial sites for 21st century opportunities. While global economics has moved mass production overseas, you will meet a few superbly talented Philadelphians who served and are serving niche markets with high quality products and services.

TEXTILES

Wool manufacture was the first enterprise to be restricted by British Colonial Rule, dating back to 1640. Other restrictions followed and in 1699 Parliament passed the so-called Woolen’s Act, prohibiting the export of, or intercolonial trade in, wool. All this legislation served to stem any possibility of “setting up Woolen Manufacture in the English plantations in America. ” 2

Philadelphia attracted the industrious and independent. William Calverly made the first carpets in America in Philadelphia in 1775, the same year the spinning jenny arrived. William Sprague made Turkish and Axminster carpets in Philadelphia as early as 1791. In 1815, W.H. Worstman manufactured the first silk in America, for trimmings. Worstman was the first to introduce the Jacquard loom to America, a machine which transformed textile manufacturing and the social order. 3

Crude frames used by 18th century home weavers were replaced by ever more sophisticated looms in the emerging weaving mills of the mid 19th century 4 ; thousands more improvements were contributed by countless others on into the 20th century. By 1909, there were 102,459 persons employed in the textile industries of Philadelphia, a twenty seven percent increase over the 80,310 employed in 1904. These Philadelphians produced more than the next three textile cities combined: Lawrence, Fall River and Lowell, all in Massachusetts. These Philadelphians produced cotton, woolen, worsted and silk goods, carpets, hosiery and knit goods valued at $215 million; consuming one-fifth of all the wool used in the United States, both domestic and foreign. Immigrants were drawn to these opportunities and Philadelphia’s population grew from 100,000 in 1835 to 1,550,000 in 1910, shaping the streets, houses and industrial buildings that we will pass. 5

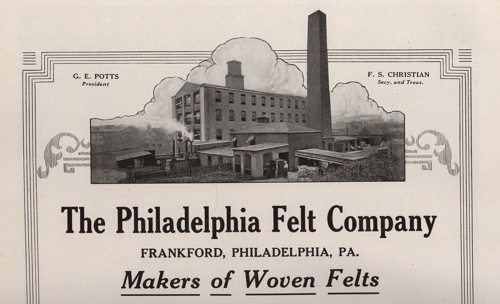

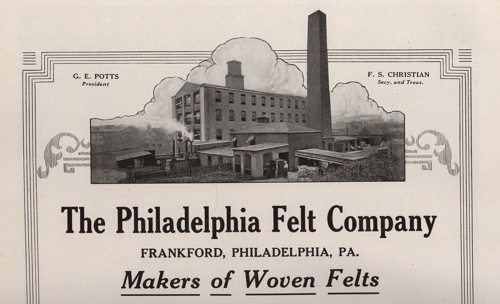

Textile manufacturers’ advertising of that time often featured impressive bird’s-eye views of their facilities, conveying a sense of solidity and dependability but a closer look at the superb Hexamer Surveys, City Atlases and various directories shows this to have been a very dynamic industry. Fortunes were made by some and their growth is recorded across many properties. Six to nine other firms might be squeezed into a single building. Compare Bromley Atlases from 1895 and 1924 to see those proud and sprawling textile complexes are owned by “Realty Cos.” and probably looking for tenants.

Details of firms that survived for less than a generation probably elude us but a concentrated effort should be made to record the stories of the surviving principals, their processes and records. Consider Globe Dye Works which was started and run by the Greenwood family from 1865-2005—the fourth and fifth generation live quietly amongst us. Thousands of industrial buildings sit seemingly entombed after decades of neglect. The decay we see around us today is the result of losing half a million residents since the population peak of two million around WWII. Penn’s original Philadelphia, what we call “Center City,” is now thriving and driving new development in the surrounding neighborhoods, presenting a growing threat to the industrial sites and their contents. Philadelphia manufacturing shaped American history and its economic success—let’s preserve those stories of industry.

HARRY LONSDALE - CHURCHVILLE FABRICS

In 2007, Lonsdale and his dedicated staff are some of the few survivors of Philadelphia’s textile industry. Production for the mass market has moved overseas, using cheap labor and threads, often including polyester, which costs one third that of nylon. American weavers face other challenges, including the weak value of the dollar to other currencies which has driven up their cost for wool, today supplied mainly from Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. Harry Lonsdale will demonstrate various weaving and finishing operations for us, then share his observations of the contemporary textile market.

“Wool is a most amazing fiber” exclaims Harry Lonsdale, a third generation weaver and felter. “It is resilient, strong, polishes, wicks moisture, insulates heat and sound, absorbs shocks, resists abrasion but does not rot, burn nor conduct electricity.” Through understanding these characteristics, hands-on technical savvy and by serving specialty markets, Lonsdale and his dedicated staff have produced an extraordinary range of products made from wool, felted and woven.

Lonsdale continues “Felt surrounds us. Felt held the ink in printing calculators. Felt seals revolving doors. Felt is used on countless industrial feed rolls. The furniture industry uses felt as backing to extend the life of their expensive wide carriage sand belts. They also use felt to burnish table tops. Felt also protects lamp bases from scratching those fine surfaces.” Lonsdale estimates he produced over 5,000 different die cut parts from felt.

The military purchased about 60% of Lonsdale’s production in the 1980s, mainly felt which was used to subdivide and seal ammunition boxes, preventing sparks from metal to metal contact. “Unscrew the detonator pin from the body of a grenade and you will find a small felt disk... But after the NASA Shuttle Challenger exploded [soon after launch in 1986] the military specifications became too cumbersome. It’s no fun making felt conform to specifications of a thousandth of an inch.”

Lonsdale produces contract upholstery for hotels and offices, designed by others and in house but his desk is covered with written requests stapled with fabric swatches from companies that supply authentic-specification parts to restore classic automobiles. Consider the 1930s era weather seals known as “windlace,” rubber tubes wrapped in fabric with a flange for tacking; made from cotton they quickly rotted. Real enthusiasts and judges at classic car competitions look at these small details to assign points and determine “best in class.”

Cotton was also used in auto upholstery. Now worn out from excessive use and its tendency to absorb perspiration, Lonsdale has woven over 500 different reproduction fabrics. “Studebaker offered about a dozen different fabrics each year. Here is a swatch from a 1950 Olds, notice the nylon. Look here, metallic threads were used a lot from ‘55-59, often with Mylar, a fine aluminum thread. And it’s not just for restorations of the well known cars like the ‘55-57 Chevy Belair and Nomad which have become so expensive. I now get requests for upholstery for the Nova and Falcon.”

Lonsdale supplies another fabric to history. In 1998, twenty thousand Union and Confederate re-enactors gathered in Gettysburg for the 135th anniversary of the disastrous infantry assault known as Pickett’s Charge which ended Lee’s campaign into Pennsylvania. For the first time since 1863 there were enough Union and Confederate soldiers for a complete one-for-one re-enactment. A further one hundred thousand people paid to watch.

Modern suppliers to this market often call themselves “sutlers,” the term for an army camp follower who peddled provisions to the soldiers. Lonsdale says “loads of crap uniforms sell for $200 but their inferior fabrics wear out quickly. Many original Civil War uniforms survive in superb shape, a testimony to their original design, superb fabrics and craftsmanship. We weave fabric for Charles Childs who has done loads of research. A great guy to do business with too.”

Childs credits his interest in re-enacting to his father and uncles who took him to the centennial commemorations of the Civil War when he was only eleven. Childs spent much of his career “working as a production guy for a modern dress manufacturer” but his hobby was researching Civil War uniforms. At the National Archives Childs found the US Army Quartermaster Manuals, compiled during the Civil War but never published. Therein are the most complete and exacting specifications; Childs concentrated on the uniforms, blankets and tentage. In the mid 1970s, seeking authentic cloth, Childs started to weave his own fabrics, producing about one yard per hour, but the “finishing” was even more time consuming.

Wool shrinks and sets when dampened and shaken, a quality frustrating to anyone who has thrown their sweater from washer to dryer. The woolen industry captured that tendency to create heavier weight cloth, to obscure the weave, to improve the lustre, handle and finish. One hundred years ago this “scouring, fulling, sponging, decating and shearing” was subcontracted to specialist firms. Childs says “I looked around for years. Lonsdale has all those weaving and finishing skills, and the equipment to recreate quality 19th century fabrics on a commercial scale.”

With Lonsdale’s fabrics, Childs went full time into making Civil War uniforms under the name County Cloth. 6 Unable to meet the demand he offered kits, fabrics and patterns (developed from his close observation of authentic uniforms and his tailoring skills). Childs says that his customers “want the best stuff, properly tailored from the best materials, not just sewn from mill ends bought by the pound.” Few recognize that a uniform constructed to original specifications will wear well for decades while cheap imitations might survive only a year—a costume rather than a uniform. Sleeping in the rain and marching around the battlefield is sure to shrink that inferior garment, a sartorial hazard, particularly revealing if in the trousers.

Walk into Lonsdale’s workshop and you might find him repairing a thread on his double-headed Jacquard loom which “can weave up to 11,600 threads with a 7-1/2 inch repeat. I could write the Declaration of Independence in fabric.” How does anyone learn all these skills? Lonsdale says “I am the third generation in America but it is likely that my grandfather was descended from a long line of weavers since that was the major activity in Bradford, England, where he emigrated from in 1893 at age 18.” [The textile industry in Bradford stretches back to the 13th century and it was renowned for the ‘Bradford system’ of weaving worsted cloth. The essential feature of a worsted yarn is straightness of fiber, in that the fibers lie parallel to each other ]. Lonsdale’s grandfather lost his first textile business during the Depression but later established the “Lonsdale Worsted Company.” Harry worked with his father and grandfather at Lonsdale Worsted until it went out of business in 1974.

Harry Lonsdale then went to work for Philadelphia Felt, owned by the Putney family and operated by Bob Putney, Jr. Philadelphia Felt produced lots of paper making felts—“we would run over a mile a minute”—but the demand for ever wider rolls required the investment of millions of dollars in new equipment, a risk the Putney family decided not to take so Philadelphia Felt closed in 1981. Lonsdale bought all the textile equipment from Philadelphia Felt, nothing related to making paper felts. In 1983 he bought all the customers, equipment and real estate of Quaker Felt. He sold Quaker Felt in 2004 and operates under the name Churchville Fabrics.

PAUL WAGNER & AMOS TOMLINSON, H. RIEHL & SON, TEXTILE MACHINERY

As they approached the age of 80, Paul and Bill Wagner warned their customers that retirement was imminent and that final orders should be placed. In flowed the work to be fulfilled by the Wagner brothers and their five employees. Bill Wagner was ready to close five years earlier but he and Paul “felt a loyalty to their long term employees, like Amos, who was our best woodworker, he made the straight rack blocks, ran grooves in the shuttles and worked on the comber boards” [the comb-like device which directs the thread under a Jacquard, it replaces the harness frame on regular looms]. Paul and Bill closed shop and left in 2003 but Amos Tomlinson stayed on to work with the new owners of the building, custom woodworkers, Matt and Ian Pappajohn.

In 1946 “out of the service and with only a high school education and a year of college on Uncle Sam” Paul Wagner and his bothers Bill & Bob joined their father (Ferdinand) and uncle (Theodore) who operated H. Riehl & Son, a textile machinery firm with roots dating back to 1850. 7 Wagner spent that first year getting the building back into shape. “Each window required 32 pieces of glass and I reglazed over 700 of them. With that experience I should have qualified for the glaziers union.” Wagner thinks the three story building at 4355 Orchard Street was built for the Wallace Wilson Hosiery Company in 1907. 8

Solving problems appeals to Wagner. “I had no desire to earn a degree, only an interest to learn plain, twill, basket weave and countless other intricacies of weave formation.” Wagner spent three years of night school studying at the Philadelphia College of Textiles and Sciences then spent over fifty years maintaining and improving textile machinery. Wagner developed his practical skills in Riehl’s complete woodworking and machine shop. Here patterns were made in wood for the foundries to cast into brass, bronze, iron and aluminum to be assembled into ever more capable textile weaving equipment. During the 1950s Wagner improved narrow fabric looms with multiple shuttles. With increasing confidence, Wagner overcame the reservations of his father and uncle to introduce label looms in the 1960s. He laughs as he describes a loom he designed to make mop heads. Wagner perfected his skills on complex Dobbie Looms and Jacquards. 9 Wagner went on to earn a patent for “a special lifting motion, it used half the parts of, yet fit on, the competitors loom frame.” Then the faster needle looms took over “needing just an operator, not a weaver.”

Phoenix Trimming ordered thirty seven shuttle looms to weave seat belts. Narricott bought looms to weave seat belts and webbing “cargo slings” for the transportation industry. Bally Ribbon bought lots of shuttles and blocks. Bally specializes in engineered woven narrow fabrics, specialty broadcloth and woven structures for medical, military, safety, industrial, aerospace and commercial applications . Wagner says “Bally are superb weavers. They can weave fabric into a spiral, like a Slinky. Made from graphite or composites I suspect they are used for the nose cones on rockets.” In his final years, Riehl rebuilt about three quarters of the Jacquards for Langhorne Carpet, renowned for their exact reproductions for Independence Hall, Colonial Williamsburg, Winterthur and private clients.

When asked about his favorite memories of his final working years, Wagner says “two things: answering questions from and demonstrating weaving techniques to various students from Philadelphia University (formerly the Philadelphia College of Textiles and Sciences where Wagner spent three years at night school) and looms to weave the bifurcated tubes used for bypass surgery” (imagine a tubular sleeve that divides like the letter ‘Y’). Single tubes had been knitted before but this bifurcated tube was woven. When Bill Wagner had open heart surgery in 2000 this bifurcated tube was used, so he walks around with a product made by a machine that they helped to design and manufacture.

Paul Wagner and Amos Tomlinson will share their experience and stories with us and explain some of the over 1,000 patterns they carved (usually coated in red or black lacquer) to build their largest looms which sold for $32,000. Their straight and circular shuttles will also be demonstrated; made from Dogwood and maple then impregnated with wax or clear shellac, these sold for $25-30 and were replaced “after having run round the clock for four years.”

The new occupants of 4355 Orchard Street include:

Brothers Matt & Ian operate Pappajohn Woodworking on the first floor, shaping custom millwork for restoration and new construction, crafting fine cabinets for kitchens and baths, plus making built-ins and doors. The Pappajohns will demonstrate a variety of cabinetmaking tools, from a bandsaw used by Riehl’s to advanced shapers and veneer presses. The results are beautifully crafted to celebrate the beauty of Pennsylvania hardwoods and imported veneers.

Gregory Augustine of August Interiors is on the second floor. Attracted by the character, space and light of this building, Augustine removed detritus and soiling but kept the patina of the maple floors, pine posts and best of all for us, he has carefully preserved and displayed a collection of Riehl foundry patterns.

Time allowing we will visit others in the building: the coffee roaster, the graphic designers, the sculptors and painters. The Pappajohns will share the challenges of purchasing an older industrial site and converting it for contemporary industrial and commercial uses.

METALS - foundries, machining and casting

Philadelphia’s largest and most famous manufactured exports are probably Baldwin locomotives, Budd car and rail bodies, and Cramp ships. During our tour we will visit a surviving relic of that industrial past, the vacant Turret & Machine Shop of Cramp Shipbuilding Co. (c. 1906, scheduled for demolition for new ramps to I-95) and visit one of Philadelphia’s newest metal working enterprises, the Ward Elicker Casting sculpture foundry.

In “Lives of the Philadelphia Engineers,” 10 Andrew Dawson examines the emergence of a new class of industrial entrepreneur, the machine builders.

“Philadelphia surpassed rival New England towns in the 1840s and for over three decades the city led in constructing heavy, custom-made steam engines, machine tools, locomotives and iron steam ships. Industrialisation required machinery and, by 1830, a distinctive and separate branch of machine building emerged to satisfy local and regional demand. The city's builders hitched their fortunes to expanding local manufacture and catered to its every need. Without the plentiful water power of eastern New England, manufacturers turned to steam engines as prime mover. Machinery constructors furnished steam engines and boilers to generate power for factories and southern plantations, blowing engines and sets of rolls for the iron furnaces of eastern Pennsylvania, looms and other textile machinery for local mills, pumping engines to deliver water to the city's inhabitants, locomotives for railroads throughout the country, high-quality machine tools to equip workshops and factories, and iron steam ships for the Navy and commercial lines that plied the oceans, coastal waterways and rivers. Builders also supplied sugar mills, mint machinery, printing presses, testing machinery, hosiery equipment and brickmaking machines. Built to customers' specifications, machines were made either individually or in small batches. Workshop owners enhanced the performance of their machines by the liberal use of cheap, locally-supplied iron that added to the weight and rigidity of the machine and so improved performance. Contemporaries labelled these heavy, custom-made machines 'Philadelphia Style,' to set them apart from the lighter, volume products of many New England workshops... But in the Twentieth century, in a world of corporate mass-production giants, as stagnation followed earlier setbacks, Philadelphia engineering became a backwater of small firms producing yesterday’s bespoke machines.”

More than just making machines, Philadelphia has a centuries old tradition of supporting the arts and artists. In 1795, the first public monument in Philadelphia was installed over the entrance to the Library Company of Philadelphia, a marble figure of Ben Franklin. The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, founded in 1805, is the nation’s oldest art museum and school of fine art. In 1872, concerned citizens who believed that art could play a role in a growing city formed the Fairmount Park Art Association to purchase, commission and maintain art works from the world’s leading sculptors including Daniel Chester French, Paul Manship, Frederick Remington, Jacques Lipschitz, Henry Moore and all three generations of the Calder family: Alexander Milne, Alexander Stirling and Alexander “Sandy.” Thousands of artworks, large and small, abstract and commemorative, are displayed throughout the city.

Philadelphia’s most famous sculpture, “William Penn” stands atop City Hall. Sculpted by Alexander Milne Calder, it is thirty six feet tall and weighs 53,000 pounds -- the largest single piece of sculpture on any building in the world. The Tacony Iron Works started casting it in 1890 and the bronze sculpture was set in place in 1894.

For the past twenty five years graduates of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Arts, the University of the Arts, Temple University and other art programs have sought experience and training in the comprehensive Johnson Atelier in Hamilton, NJ, founded by J. Seward Johnson who believed “There is no art more dependent on it’s technical aspects than sculpture. An ignorance of technique limits a sculptor’s creativity, wastes hours of work in bringing a cast to likeness of the original, and renders the artist captive of the foundry’s trade secrecy and commercialism. Until the Industrial Revolution, however, the opposite was true. The home of the foundry was the sculptor’s studio where the results of poor practices and errors in judgement were immediately visited upon the artist, for it was the artist who created and cast their own work. This system led to quality and efficiency.”

Johnson wanted to “restore the link and the interplay which used to exist between the sculptor and the founding of their work” with the goal “to educate and train more artisans to be available to aid the sculptor in completing their task, to develop methods for making these processes less costly and more responsive to the sculptor’s needs, and finally, to play a small part in whatever forces must come together to bring more sculpture into the 20th century lifestyle.” 11 When the Johnson Atelier was reorganized a few years ago some of their highly skilled staff artists and artisans built their own small foundries in Philadelphia.

Jeb Wood, CEO and Metalsmith of Ward Elicker Casting will give us a tour of the foundry and explain the entire process of translating an artist’s work (often in clay) into a finished sculpture in bronze or iron. Known as “lost wax casting” the process involves making the mould, making the wax casting, chasing the wax, spruing, casting the ceramic mould, burn out, casting, break out, sandblasting, assembly, chasing, glass beading, polish, patina, waxing, mounting and inspection. Elicker Casting serves emerging artists (some rent space in the building) and renowned contemporary sculptors like Tom Otterness, Julian Schnable, George Segal and Kiki Smith. [Note: photography is limited here due to contractual agreements with various galleries. Permission must be received prior to taking any photos.]

CRAMP SHIPYARD

“From these ways shall go forth ships embodying the best designs, built with speed and pride by artisans of many trades, to serve mankind in peace and war, upon the seven seas.” 12

Established in 1830, little if anything survives from the early shipbuilding years of William Cramp (1807-1879). His son, Charles Cramp (1828-1913) is considered one of America’s finest nautical engineers. Charles built the first screw-propelled tugboat in the US, the 80-foot Sampson in 1846, with engines provided by his neighbor, Neafie & Levy. In late 1862 Cramp launched New Ironsides for the Union fleet, a composite wooden ship with steam engine, screw propellor and four inches of iron plating. She was capable of sailing in the open seas, unlike the monitors. During the 1870s Cramp made the successful transition from making wood to iron vessels and then started making their own steam engines. Cramp went on to develop a successful competitor to Britain’s Atlantic Greyhounds , the fast steam vessels which handled the majority of passenger and mail service. In 1891 Cramp purchased the I.P. Morris Company, engine manufacturer; a year later the firm acquired a brass foundry for developing new allows that were being introduced into marine construction; and by 1900 Cramp had purchased the Charles Hillman Ship and Engine Building Company which was reorganized and incorporated as the Kensington Shipyard Company, comprising the drydock, ship railways, and repair yard at the foot of Palmer Street. That same year the Cramp firm upgraded its machine shop and power plant. In 1915-16 the company again made extensive capital improvements including a new mold loft and cranes. The original 10-acre site had grown to 60 acres. But when government orders declined in the ealrly 1920s, Cramp was forced to relinquish its shipbuilding activities. 13

[Reprinted below is a thorough description of the revitalization during WWII, published in Cramp Shipbuilding Company, 1940-1944 ].

Cramp Shipyard has a venerable history dating back to the year 1830, when it was founded by William Cramp. As the years went by, the yard grew until during the first World War it covered 59 acres and employed some 10,500 marine workers. In 1927, owing to lack of work and unfavorable conditions in the ship-building industry, the ninety-seven-year-old Company decided to give up the marine business, sell its tools and equipment, separate its non-marine departments and subsidiaries, and close its gates. Thirteen years later, in 1940, the present company, the Cramp Shipbuilding Company, was established with the approval of the Secretary of the Navy in order to undertake the reopening of the old Cramp Shipyard for the construction of urgently needed ships of war for the United States Navy. The reopening of the yard was accomplished with a minimum of delay as a result of the effort of the newly born company working in close co-operation with the Navy Department.

Accordingly, with the co-operation and financial assistance of the Navy Department, a program for reopening the historic shipyard was evolved and under-written by Harriman Ripley & Co., Incorporated, so as to permit it again to take its place among the foremost shipbuilding and ship repair yards of this country. The yard was reopened in October, 1940. After Pearl Harbor the facilities program, at the request of the Navy, was greatly enlarged with naval funds so as to include a concrete dry dock and repair base and facilities for submarine construction.

At the time of reopening, although the plant was in a rather dilapidated condition, there remained, in a fairly good state of preservation, two large concrete ship-ways and two small shipways, a large wet dock with servicing cranes, shipway cranes, a fabricating shop, a large office building, an outfitting building, and other useful structures. The real estate, with its excellent water front on the Delaware River, was of great value. In the adjacent Kensington district, one of the finest industrial sections in the country, there have always resided many workmen skilled in the arts of shipbuilding. Consequently, the shipyard was never faced with a housing problem.

At present, the yard, employing over 15,000 men and women, covers some 65 acres, not including leased storage space; and the former facilities have been replaced, enlarged, or rebuilt to such an extent that if the ghosts of William Cramp and his sons were to appear they would hardly recognize the old stamping ground. The planners of the new Cramp Shipbuilding Company reconstructed the plant with an eye to "streamlining" production. Old buildings poorly located were demolished, while new ones were added to suit the scheme. Arrangement was designed to approximate the "production line" system of construction. Although a ship cannot be moved during its construction like an automobile or a refrigerator, it is possible to apply "production line" methods to the movement of its parts as they go down from the storage yards to the ways. The present layout of the Cramp Yard was so carefully planned that it has become an extremely effective setup for building ships.

One may attain the idea of the "production line" scheme from a brief description of the yard. Richmond Street, along which the property extends for some 1,300 feet, is approximately parallel to the Delaware River; the buildings generally run parallel to both. The area occupied between the street and the water is about 60 acres. At the south end of the property, along Richmond Street, is a long two-story structure containing a receiving department, stores, a trade and a testing laboratory. Adjacent to this is a nine-story administration building. Here are located the drafting rooms, the Navy headquarters, and the main offices. North of this building are an entrance gate, a timekeeper's office, a reproduction department, a guard house, a rigging loft, and at the north corner, a large pipe shop. Between these buildings and the water front are the outside steel-storage racks, the main fabricating shop, and the pre-assembly platens. These three extensive areas reach practically from one end of the yard to the other. A crane system traverses the entire space, so that steel may be carried from the storage racks directly into the south end of the fabricating shop, formed and partially assembled, then carried by the same cranes northward to the pre-assembly platens, where it can be welded into structures as large as the overhead bridge cranes will carry. Thence the assemblies can be carried by bridge cranes down to the shipways and joined together into hulls. The bridge cranes are capable of carrying assemblies of approximately 75 tons directly from the platens down to the shipways without interference.

The efficiency of this method of handling material is considerably greater than that achieved in former days, for steel may thus be moved to any desired position while being assembled. In the old days, only small and minor pre-assembled sections were taken to the vessels on the ways.

Along the water front are located the new graving dock, a series of outfitting piers, modern concrete shipways capable of accommodating vessels from 650 to 700 feet long, and to the extreme north, the large wet basin. This basin is served by three hammerhead cranes. At the head of the wet basin are the electrical shop, the outside machine shop, the sheet metal shop, and the shipwright and carpenter shop. Also located in this vicinity are the paint shop and the out-fitting stores building.

A second fabricating shop, smaller than the main fabricating shop, is located between the shipways and the dry dock. Most of this shop is used for the assembly of large fabricated sections of submarines. The submarine program has become so extensive that it has been found necessary to devote special facilities to the construction of hull sections for these vessels alone. A forge shop is also located in the smaller fabricating shop. It is planned that this shop will eventually be used for other types of vessels.

On the other side of Richmond Street, on a triangular plot, stands the large building which houses the turret and machine shops. This structure alone covers more than 3 1/2 acres.

A network of railroad tracks connects the various buildings with the Pennsylvania and Reading lines.

In order that our nation may receive the support which it requires today, the shipyard is carrying on its honorable tradition by throwing the full weight of its efforts into the task of building up the Navy.

BEER

Kensington and Northern Liberties was home to many brewers including Christian Schmidt, Theodore Finkenauer, Frederick Feil, John Roehm, Joseph Rieger, William Heimgaertner, Albert Wolf, John Wagner and generations of Ortliebs. We will pass a few of the surviving brewing buildings, most near ruin. A rare survivor in decent shape is the “Emil Schaefer—Copper, Brass and Iron Works, Manufacturer of Brewers, Distillers and Sugar Refining Apparatus” at 1321-1312 North Randolph Street.

Yards Brewing purchased the former Weisbrod & Hess Brewery in May 2001 and started brewing beer in March 2002. Brewing capacity has grown from 2,500 barrels to 8,000 barrels in 2006. All brewing starts with 30 barrels; mixed into 60 barrel fermenters. Half the production is of Philadelphia Pale Ale, "a Pale Ale brewed with a Pilsner malt." Other beers brewed regularly include India Pale Ale, Extra Special Ale, Saison and three "Ales of the Revolution" brewed according to the historic recipes of three founding fathers: General Washington Porter, Thomas Jefferson Tavern Ale and Poor Richard's Tavern Spruce [Ben Franklin]. Yards uses Simcoe hops from the Yakima Valley region of Washington state and malts from the US and Germany. Yards sells direct to over 330 accounts in the Philadelphia area and this high local demand has restricted the availability elsewhere. Tastings will be offered.

Yards was started by John Bovit and Tom Kehoe in 1995 in Manayunk, moving eighteen months later Roxborough. In 1998. Bovit left and Kehoe (President) was joined by Nancy Barton (Secretary-Treasurer) and her husband Bill Barton (Vice President). Thirteen people are on the Yards staff including head brewer Josh Ervine, the "Parson of Fermentation" Dean Brown [a skilled brewer] and "The Enabler" Chris Morris [Sales Manager]. It was the Barton's who found this building, noticing the "Bottling Plant" sign after delivering beer to a local customer. The complex was then stuffed with used supermarket equipment—deli cases, carts, shelving, scales—offered for resale.

Yards brews on the second floor of the former W&H Bottling Plant and the gently sloping concrete floors and two original floor drains still serve their original purpose (large windows to the west offer a rooftop glimpse to a concentrated collection of Kensington mill buildings clustered near Coral and Front Streets). Bottling is done downstairs on a line requiring five pairs of hands. Kegging can be done by one. The Bartons have visited breweries in Europe and hosted Brew Masters at Yards to learn how to increase capacity within the building; they now estimate they can grow to between 20,000 and 40,000 barrels per year. The packaging and shipping room is on the first floor of the building to the north of the courtyard while the office and tasting room are above (often used by community groups as meeting space).

1 Samuel Needles, “ The Governor’s Mill, and the Globe Mills, Philadelphia,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 8, pp. 279-299, 377-390.

2 Werner von Bergen & Herbert R. Mauersberger, American Wool Handbook (Textile Book Publishers, NY, 1948), p. 5

3 For more information on the early textile industry in Philadelphia read chapter 7, “Manayunk, an overview” in Workshop of the World , (Oliver Evans Press, 1990).

4 Weaving, knitting, braiding, etc. were separate operations often done in separate establishments or “mills.”

5 John James MacFarlane, Textile Industries of Philadelphia (Philadelphia Commercial Museum, 1910).

6 Charles Childs, County Cloth, Paris, Ohio

7 “In 1850, W.C. Clark began business, and soon afterwards Messrs. Chambers & Riehl opened a similar establishment. In 1871 the two concerns were consolidated under the firm style of Riehl & Clark... There works comprise a three story building 22 x 50 feet... Twelve skilled and experienced hands are employed, and the concern is kept busy in supplying jacquard, swivel and hand looms, as well as fly lathes and jacquard machines, to mills located in Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Delaware... The house, in addition to manufacturing looms, etc. also makes to order and has on hand a general assortment of weaver’s utensils... No. 1130 Charlotte Street, above George Street.” [Illustrated Philadelphia” p. 234]. Edwin Trowell Freedley in Philadelphia and its Manufactures , gives the address as “1033 N. 4th Street , bet. Poplar & George.” Early H. Riehl & Son advertising states “1130 & 1132 Charlotte Street” where Paul Wagner worked as a boy before Riehl moved to 4355 Orchard Street in 1946. Charlotte Street was the former name of Orianna Street. The name of the firm evolved to Riehl & Clark, Henry Riehl then H. Riehl & Son. August Wagner (Paul’s grandfather) worked for Riehl & Son, then slowly bought into the business from Henry Riehl’s son, acquiring the company and name in 1940. August’s two youngest sons, Ferdinand and Theodore took over the business. In 1949, Ferdinand’s sons (Paul, Bill and Bob) bought into the business. They bought out Ferdinand’s interest in 1973, Theodores’s in 1975 and later, the ten percent interest of their bookkeeper Lou Rick. Bob has passed away in 1987.

8 “1895” is visible on the left side of the front facade between the second and third floor windows. A similar but now illegible mark is on the right side. There are longer illegible marks between the first and second floor windows. Paul Wagner remembers the date “1907” and the wording “Established...[and possibly Wallace Wilson Hosiery Co.]” and says these were covered over in red cement after WWII when the Wagners took over the building and wanted to promote H. Riehl & Son. Wagner says that Wallace Wilson Hosiery started in the back buildings and one lost to fire, just to the north, 4342 N. Waln Street, so “1895” might be their founding date and the obscured date, remembered as “1907” might signifying the construction date of the large three-story building. The Directory of Textile and Yarn Manufacturers of Philadelphia of 1910 does list “Wallace Wilson Hosiery Co, Orchard St. below Unity.” For information on the older buildings on this site see Workshop of the World (Oliver Evans Press, 1990), “Spring Mills,” item 15.6.

9 Jacquards were o ften bought from Thomas Halton & Sons, 2nd & Allegheny, until they went out of business around 1980.

10 Andrew Dawson, Lives of the Philadelphia Engineers, Capital, Class and Revolution, 1830-1890, Ashgate, 2004), p. 2-3.

11 excerpted from J. Seward Johnson’s Founder’s Statement , Johnson Atelier, at www.atelier.org

12 motto of Cramp Shipyard

13 see Gail E. Farr, Shipbuilding at Cramp & Sons: A History 1830-1946

Tour leader: Torben Jenk

1215 Unity Street, former site of Quaker Felt.

Harry Lonsdale, Churchville Fabrics, weaving and textile finishing.

4355 Orchard Street, former site of “H. Riehl & Son,” Textile Machinery.

Paul Wagner, former owner of Riehl.

Matt & Ian Pappajohn, Pappajohn Woodworking, millwork & cabinetmakers.

Gregory August, August Interiors, conservator of Riehl patterns.

2439 Amber Street, former site of Weisbrod & Hess Brewery (1882-1938).

Tom Kehoe, Nancy & Bill Barton, owners and operators of Yards Brewing.

3450 J Street, former site of Luithlen Dye.

Jeb Wood, Ward Elicker Casting, sculpture foundry.

2050 Richmond Street, former Turret & Machine Shop of Cramp Shipbuilding Company.

Joel Assouline, Assouline & Ting, distributor of gourmet foods.

Kensington & Fishtown riverfront: Penn Treaty Park, former site of Neafie & Levy, misc. shipways and Cramp Graving Dock (filled in).

INTRODUCTION

Fearful of fire and filth, William Penn excluded industrial activities from his “Greene Countrie Towne” from the beginnings in 1681. But Penn had industrial interests, writing in 1701 “Get my two mills finished and make the most of these for my profit, but let not John Marsh put me to any great expense.” By 1708 Penn laments “Our mill proves the unhappiest thing of the kind, that ever man, I think, was engaged in. If ill luck can attend any place more than another it may claim a charter for it. I wish it were sold.” It was, in 1714, to Thomas Masters who, in 1715, received t he first patent issued to any person in the American Colonies “for the sole Use and Benefit of A New Invencon found out by Sybilla, his wife, for Cleaning and Curing the Indian Corn growing in the severall Colonies in America...” 1

So began the industrial activity in the ancient neighborhoods of Northern Liberties, Kensington and Frankford. In 1787, John Fitch and his “superior Mechanical Genius” Henry Voight fashioned boilers and chains to propel the first steam boat. Improved foundry techniques allowed early locomotives to be built here in the 1830s, followed by Charles Cramp’s massive steam ships. Cheers to all that hard work, John Wagner brewed the first lager beer in America, behind his house, in 1840. Industrial activity across many of the twenty seven districts of Philadelphia County made this the largest center of machine building in 19th century America. Only upon consolidating these productive neighborhoods in 1854 could the City of Philadelphia claim its title as “Workshop of the World.”

On our tour we will learn about long lost enterprises, visit active manufacturers, meet generations of entrepreneurs and experience the rebirth of centuries-old industrial sites for 21st century opportunities. While global economics has moved mass production overseas, you will meet a few superbly talented Philadelphians who served and are serving niche markets with high quality products and services.

TEXTILES

Wool manufacture was the first enterprise to be restricted by British Colonial Rule, dating back to 1640. Other restrictions followed and in 1699 Parliament passed the so-called Woolen’s Act, prohibiting the export of, or intercolonial trade in, wool. All this legislation served to stem any possibility of “setting up Woolen Manufacture in the English plantations in America. ” 2

Philadelphia attracted the industrious and independent. William Calverly made the first carpets in America in Philadelphia in 1775, the same year the spinning jenny arrived. William Sprague made Turkish and Axminster carpets in Philadelphia as early as 1791. In 1815, W.H. Worstman manufactured the first silk in America, for trimmings. Worstman was the first to introduce the Jacquard loom to America, a machine which transformed textile manufacturing and the social order. 3

Crude frames used by 18th century home weavers were replaced by ever more sophisticated looms in the emerging weaving mills of the mid 19th century 4 ; thousands more improvements were contributed by countless others on into the 20th century. By 1909, there were 102,459 persons employed in the textile industries of Philadelphia, a twenty seven percent increase over the 80,310 employed in 1904. These Philadelphians produced more than the next three textile cities combined: Lawrence, Fall River and Lowell, all in Massachusetts. These Philadelphians produced cotton, woolen, worsted and silk goods, carpets, hosiery and knit goods valued at $215 million; consuming one-fifth of all the wool used in the United States, both domestic and foreign. Immigrants were drawn to these opportunities and Philadelphia’s population grew from 100,000 in 1835 to 1,550,000 in 1910, shaping the streets, houses and industrial buildings that we will pass. 5

Textile manufacturers’ advertising of that time often featured impressive bird’s-eye views of their facilities, conveying a sense of solidity and dependability but a closer look at the superb Hexamer Surveys, City Atlases and various directories shows this to have been a very dynamic industry. Fortunes were made by some and their growth is recorded across many properties. Six to nine other firms might be squeezed into a single building. Compare Bromley Atlases from 1895 and 1924 to see those proud and sprawling textile complexes are owned by “Realty Cos.” and probably looking for tenants.

Details of firms that survived for less than a generation probably elude us but a concentrated effort should be made to record the stories of the surviving principals, their processes and records. Consider Globe Dye Works which was started and run by the Greenwood family from 1865-2005—the fourth and fifth generation live quietly amongst us. Thousands of industrial buildings sit seemingly entombed after decades of neglect. The decay we see around us today is the result of losing half a million residents since the population peak of two million around WWII. Penn’s original Philadelphia, what we call “Center City,” is now thriving and driving new development in the surrounding neighborhoods, presenting a growing threat to the industrial sites and their contents. Philadelphia manufacturing shaped American history and its economic success—let’s preserve those stories of industry.

HARRY LONSDALE - CHURCHVILLE FABRICS

In 2007, Lonsdale and his dedicated staff are some of the few survivors of Philadelphia’s textile industry. Production for the mass market has moved overseas, using cheap labor and threads, often including polyester, which costs one third that of nylon. American weavers face other challenges, including the weak value of the dollar to other currencies which has driven up their cost for wool, today supplied mainly from Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. Harry Lonsdale will demonstrate various weaving and finishing operations for us, then share his observations of the contemporary textile market.

“Wool is a most amazing fiber” exclaims Harry Lonsdale, a third generation weaver and felter. “It is resilient, strong, polishes, wicks moisture, insulates heat and sound, absorbs shocks, resists abrasion but does not rot, burn nor conduct electricity.” Through understanding these characteristics, hands-on technical savvy and by serving specialty markets, Lonsdale and his dedicated staff have produced an extraordinary range of products made from wool, felted and woven.

Lonsdale continues “Felt surrounds us. Felt held the ink in printing calculators. Felt seals revolving doors. Felt is used on countless industrial feed rolls. The furniture industry uses felt as backing to extend the life of their expensive wide carriage sand belts. They also use felt to burnish table tops. Felt also protects lamp bases from scratching those fine surfaces.” Lonsdale estimates he produced over 5,000 different die cut parts from felt.

The military purchased about 60% of Lonsdale’s production in the 1980s, mainly felt which was used to subdivide and seal ammunition boxes, preventing sparks from metal to metal contact. “Unscrew the detonator pin from the body of a grenade and you will find a small felt disk... But after the NASA Shuttle Challenger exploded [soon after launch in 1986] the military specifications became too cumbersome. It’s no fun making felt conform to specifications of a thousandth of an inch.”

Lonsdale produces contract upholstery for hotels and offices, designed by others and in house but his desk is covered with written requests stapled with fabric swatches from companies that supply authentic-specification parts to restore classic automobiles. Consider the 1930s era weather seals known as “windlace,” rubber tubes wrapped in fabric with a flange for tacking; made from cotton they quickly rotted. Real enthusiasts and judges at classic car competitions look at these small details to assign points and determine “best in class.”

Cotton was also used in auto upholstery. Now worn out from excessive use and its tendency to absorb perspiration, Lonsdale has woven over 500 different reproduction fabrics. “Studebaker offered about a dozen different fabrics each year. Here is a swatch from a 1950 Olds, notice the nylon. Look here, metallic threads were used a lot from ‘55-59, often with Mylar, a fine aluminum thread. And it’s not just for restorations of the well known cars like the ‘55-57 Chevy Belair and Nomad which have become so expensive. I now get requests for upholstery for the Nova and Falcon.”

Lonsdale supplies another fabric to history. In 1998, twenty thousand Union and Confederate re-enactors gathered in Gettysburg for the 135th anniversary of the disastrous infantry assault known as Pickett’s Charge which ended Lee’s campaign into Pennsylvania. For the first time since 1863 there were enough Union and Confederate soldiers for a complete one-for-one re-enactment. A further one hundred thousand people paid to watch.

Modern suppliers to this market often call themselves “sutlers,” the term for an army camp follower who peddled provisions to the soldiers. Lonsdale says “loads of crap uniforms sell for $200 but their inferior fabrics wear out quickly. Many original Civil War uniforms survive in superb shape, a testimony to their original design, superb fabrics and craftsmanship. We weave fabric for Charles Childs who has done loads of research. A great guy to do business with too.”

Childs credits his interest in re-enacting to his father and uncles who took him to the centennial commemorations of the Civil War when he was only eleven. Childs spent much of his career “working as a production guy for a modern dress manufacturer” but his hobby was researching Civil War uniforms. At the National Archives Childs found the US Army Quartermaster Manuals, compiled during the Civil War but never published. Therein are the most complete and exacting specifications; Childs concentrated on the uniforms, blankets and tentage. In the mid 1970s, seeking authentic cloth, Childs started to weave his own fabrics, producing about one yard per hour, but the “finishing” was even more time consuming.

Wool shrinks and sets when dampened and shaken, a quality frustrating to anyone who has thrown their sweater from washer to dryer. The woolen industry captured that tendency to create heavier weight cloth, to obscure the weave, to improve the lustre, handle and finish. One hundred years ago this “scouring, fulling, sponging, decating and shearing” was subcontracted to specialist firms. Childs says “I looked around for years. Lonsdale has all those weaving and finishing skills, and the equipment to recreate quality 19th century fabrics on a commercial scale.”

With Lonsdale’s fabrics, Childs went full time into making Civil War uniforms under the name County Cloth. 6 Unable to meet the demand he offered kits, fabrics and patterns (developed from his close observation of authentic uniforms and his tailoring skills). Childs says that his customers “want the best stuff, properly tailored from the best materials, not just sewn from mill ends bought by the pound.” Few recognize that a uniform constructed to original specifications will wear well for decades while cheap imitations might survive only a year—a costume rather than a uniform. Sleeping in the rain and marching around the battlefield is sure to shrink that inferior garment, a sartorial hazard, particularly revealing if in the trousers.

Walk into Lonsdale’s workshop and you might find him repairing a thread on his double-headed Jacquard loom which “can weave up to 11,600 threads with a 7-1/2 inch repeat. I could write the Declaration of Independence in fabric.” How does anyone learn all these skills? Lonsdale says “I am the third generation in America but it is likely that my grandfather was descended from a long line of weavers since that was the major activity in Bradford, England, where he emigrated from in 1893 at age 18.” [The textile industry in Bradford stretches back to the 13th century and it was renowned for the ‘Bradford system’ of weaving worsted cloth. The essential feature of a worsted yarn is straightness of fiber, in that the fibers lie parallel to each other ]. Lonsdale’s grandfather lost his first textile business during the Depression but later established the “Lonsdale Worsted Company.” Harry worked with his father and grandfather at Lonsdale Worsted until it went out of business in 1974.

Harry Lonsdale then went to work for Philadelphia Felt, owned by the Putney family and operated by Bob Putney, Jr. Philadelphia Felt produced lots of paper making felts—“we would run over a mile a minute”—but the demand for ever wider rolls required the investment of millions of dollars in new equipment, a risk the Putney family decided not to take so Philadelphia Felt closed in 1981. Lonsdale bought all the textile equipment from Philadelphia Felt, nothing related to making paper felts. In 1983 he bought all the customers, equipment and real estate of Quaker Felt. He sold Quaker Felt in 2004 and operates under the name Churchville Fabrics.

PAUL WAGNER & AMOS TOMLINSON, H. RIEHL & SON, TEXTILE MACHINERY

As they approached the age of 80, Paul and Bill Wagner warned their customers that retirement was imminent and that final orders should be placed. In flowed the work to be fulfilled by the Wagner brothers and their five employees. Bill Wagner was ready to close five years earlier but he and Paul “felt a loyalty to their long term employees, like Amos, who was our best woodworker, he made the straight rack blocks, ran grooves in the shuttles and worked on the comber boards” [the comb-like device which directs the thread under a Jacquard, it replaces the harness frame on regular looms]. Paul and Bill closed shop and left in 2003 but Amos Tomlinson stayed on to work with the new owners of the building, custom woodworkers, Matt and Ian Pappajohn.

In 1946 “out of the service and with only a high school education and a year of college on Uncle Sam” Paul Wagner and his bothers Bill & Bob joined their father (Ferdinand) and uncle (Theodore) who operated H. Riehl & Son, a textile machinery firm with roots dating back to 1850. 7 Wagner spent that first year getting the building back into shape. “Each window required 32 pieces of glass and I reglazed over 700 of them. With that experience I should have qualified for the glaziers union.” Wagner thinks the three story building at 4355 Orchard Street was built for the Wallace Wilson Hosiery Company in 1907. 8

Solving problems appeals to Wagner. “I had no desire to earn a degree, only an interest to learn plain, twill, basket weave and countless other intricacies of weave formation.” Wagner spent three years of night school studying at the Philadelphia College of Textiles and Sciences then spent over fifty years maintaining and improving textile machinery. Wagner developed his practical skills in Riehl’s complete woodworking and machine shop. Here patterns were made in wood for the foundries to cast into brass, bronze, iron and aluminum to be assembled into ever more capable textile weaving equipment. During the 1950s Wagner improved narrow fabric looms with multiple shuttles. With increasing confidence, Wagner overcame the reservations of his father and uncle to introduce label looms in the 1960s. He laughs as he describes a loom he designed to make mop heads. Wagner perfected his skills on complex Dobbie Looms and Jacquards. 9 Wagner went on to earn a patent for “a special lifting motion, it used half the parts of, yet fit on, the competitors loom frame.” Then the faster needle looms took over “needing just an operator, not a weaver.”

Phoenix Trimming ordered thirty seven shuttle looms to weave seat belts. Narricott bought looms to weave seat belts and webbing “cargo slings” for the transportation industry. Bally Ribbon bought lots of shuttles and blocks. Bally specializes in engineered woven narrow fabrics, specialty broadcloth and woven structures for medical, military, safety, industrial, aerospace and commercial applications . Wagner says “Bally are superb weavers. They can weave fabric into a spiral, like a Slinky. Made from graphite or composites I suspect they are used for the nose cones on rockets.” In his final years, Riehl rebuilt about three quarters of the Jacquards for Langhorne Carpet, renowned for their exact reproductions for Independence Hall, Colonial Williamsburg, Winterthur and private clients.

When asked about his favorite memories of his final working years, Wagner says “two things: answering questions from and demonstrating weaving techniques to various students from Philadelphia University (formerly the Philadelphia College of Textiles and Sciences where Wagner spent three years at night school) and looms to weave the bifurcated tubes used for bypass surgery” (imagine a tubular sleeve that divides like the letter ‘Y’). Single tubes had been knitted before but this bifurcated tube was woven. When Bill Wagner had open heart surgery in 2000 this bifurcated tube was used, so he walks around with a product made by a machine that they helped to design and manufacture.

Paul Wagner and Amos Tomlinson will share their experience and stories with us and explain some of the over 1,000 patterns they carved (usually coated in red or black lacquer) to build their largest looms which sold for $32,000. Their straight and circular shuttles will also be demonstrated; made from Dogwood and maple then impregnated with wax or clear shellac, these sold for $25-30 and were replaced “after having run round the clock for four years.”

The new occupants of 4355 Orchard Street include:

Brothers Matt & Ian operate Pappajohn Woodworking on the first floor, shaping custom millwork for restoration and new construction, crafting fine cabinets for kitchens and baths, plus making built-ins and doors. The Pappajohns will demonstrate a variety of cabinetmaking tools, from a bandsaw used by Riehl’s to advanced shapers and veneer presses. The results are beautifully crafted to celebrate the beauty of Pennsylvania hardwoods and imported veneers.

Gregory Augustine of August Interiors is on the second floor. Attracted by the character, space and light of this building, Augustine removed detritus and soiling but kept the patina of the maple floors, pine posts and best of all for us, he has carefully preserved and displayed a collection of Riehl foundry patterns.

Time allowing we will visit others in the building: the coffee roaster, the graphic designers, the sculptors and painters. The Pappajohns will share the challenges of purchasing an older industrial site and converting it for contemporary industrial and commercial uses.

METALS - foundries, machining and casting

Philadelphia’s largest and most famous manufactured exports are probably Baldwin locomotives, Budd car and rail bodies, and Cramp ships. During our tour we will visit a surviving relic of that industrial past, the vacant Turret & Machine Shop of Cramp Shipbuilding Co. (c. 1906, scheduled for demolition for new ramps to I-95) and visit one of Philadelphia’s newest metal working enterprises, the Ward Elicker Casting sculpture foundry.

In “Lives of the Philadelphia Engineers,” 10 Andrew Dawson examines the emergence of a new class of industrial entrepreneur, the machine builders.

“Philadelphia surpassed rival New England towns in the 1840s and for over three decades the city led in constructing heavy, custom-made steam engines, machine tools, locomotives and iron steam ships. Industrialisation required machinery and, by 1830, a distinctive and separate branch of machine building emerged to satisfy local and regional demand. The city's builders hitched their fortunes to expanding local manufacture and catered to its every need. Without the plentiful water power of eastern New England, manufacturers turned to steam engines as prime mover. Machinery constructors furnished steam engines and boilers to generate power for factories and southern plantations, blowing engines and sets of rolls for the iron furnaces of eastern Pennsylvania, looms and other textile machinery for local mills, pumping engines to deliver water to the city's inhabitants, locomotives for railroads throughout the country, high-quality machine tools to equip workshops and factories, and iron steam ships for the Navy and commercial lines that plied the oceans, coastal waterways and rivers. Builders also supplied sugar mills, mint machinery, printing presses, testing machinery, hosiery equipment and brickmaking machines. Built to customers' specifications, machines were made either individually or in small batches. Workshop owners enhanced the performance of their machines by the liberal use of cheap, locally-supplied iron that added to the weight and rigidity of the machine and so improved performance. Contemporaries labelled these heavy, custom-made machines 'Philadelphia Style,' to set them apart from the lighter, volume products of many New England workshops... But in the Twentieth century, in a world of corporate mass-production giants, as stagnation followed earlier setbacks, Philadelphia engineering became a backwater of small firms producing yesterday’s bespoke machines.”

More than just making machines, Philadelphia has a centuries old tradition of supporting the arts and artists. In 1795, the first public monument in Philadelphia was installed over the entrance to the Library Company of Philadelphia, a marble figure of Ben Franklin. The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, founded in 1805, is the nation’s oldest art museum and school of fine art. In 1872, concerned citizens who believed that art could play a role in a growing city formed the Fairmount Park Art Association to purchase, commission and maintain art works from the world’s leading sculptors including Daniel Chester French, Paul Manship, Frederick Remington, Jacques Lipschitz, Henry Moore and all three generations of the Calder family: Alexander Milne, Alexander Stirling and Alexander “Sandy.” Thousands of artworks, large and small, abstract and commemorative, are displayed throughout the city.

Philadelphia’s most famous sculpture, “William Penn” stands atop City Hall. Sculpted by Alexander Milne Calder, it is thirty six feet tall and weighs 53,000 pounds -- the largest single piece of sculpture on any building in the world. The Tacony Iron Works started casting it in 1890 and the bronze sculpture was set in place in 1894.

For the past twenty five years graduates of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Arts, the University of the Arts, Temple University and other art programs have sought experience and training in the comprehensive Johnson Atelier in Hamilton, NJ, founded by J. Seward Johnson who believed “There is no art more dependent on it’s technical aspects than sculpture. An ignorance of technique limits a sculptor’s creativity, wastes hours of work in bringing a cast to likeness of the original, and renders the artist captive of the foundry’s trade secrecy and commercialism. Until the Industrial Revolution, however, the opposite was true. The home of the foundry was the sculptor’s studio where the results of poor practices and errors in judgement were immediately visited upon the artist, for it was the artist who created and cast their own work. This system led to quality and efficiency.”

Johnson wanted to “restore the link and the interplay which used to exist between the sculptor and the founding of their work” with the goal “to educate and train more artisans to be available to aid the sculptor in completing their task, to develop methods for making these processes less costly and more responsive to the sculptor’s needs, and finally, to play a small part in whatever forces must come together to bring more sculpture into the 20th century lifestyle.” 11 When the Johnson Atelier was reorganized a few years ago some of their highly skilled staff artists and artisans built their own small foundries in Philadelphia.

Jeb Wood, CEO and Metalsmith of Ward Elicker Casting will give us a tour of the foundry and explain the entire process of translating an artist’s work (often in clay) into a finished sculpture in bronze or iron. Known as “lost wax casting” the process involves making the mould, making the wax casting, chasing the wax, spruing, casting the ceramic mould, burn out, casting, break out, sandblasting, assembly, chasing, glass beading, polish, patina, waxing, mounting and inspection. Elicker Casting serves emerging artists (some rent space in the building) and renowned contemporary sculptors like Tom Otterness, Julian Schnable, George Segal and Kiki Smith. [Note: photography is limited here due to contractual agreements with various galleries. Permission must be received prior to taking any photos.]

CRAMP SHIPYARD

“From these ways shall go forth ships embodying the best designs, built with speed and pride by artisans of many trades, to serve mankind in peace and war, upon the seven seas.” 12

Established in 1830, little if anything survives from the early shipbuilding years of William Cramp (1807-1879). His son, Charles Cramp (1828-1913) is considered one of America’s finest nautical engineers. Charles built the first screw-propelled tugboat in the US, the 80-foot Sampson in 1846, with engines provided by his neighbor, Neafie & Levy. In late 1862 Cramp launched New Ironsides for the Union fleet, a composite wooden ship with steam engine, screw propellor and four inches of iron plating. She was capable of sailing in the open seas, unlike the monitors. During the 1870s Cramp made the successful transition from making wood to iron vessels and then started making their own steam engines. Cramp went on to develop a successful competitor to Britain’s Atlantic Greyhounds , the fast steam vessels which handled the majority of passenger and mail service. In 1891 Cramp purchased the I.P. Morris Company, engine manufacturer; a year later the firm acquired a brass foundry for developing new allows that were being introduced into marine construction; and by 1900 Cramp had purchased the Charles Hillman Ship and Engine Building Company which was reorganized and incorporated as the Kensington Shipyard Company, comprising the drydock, ship railways, and repair yard at the foot of Palmer Street. That same year the Cramp firm upgraded its machine shop and power plant. In 1915-16 the company again made extensive capital improvements including a new mold loft and cranes. The original 10-acre site had grown to 60 acres. But when government orders declined in the ealrly 1920s, Cramp was forced to relinquish its shipbuilding activities. 13

[Reprinted below is a thorough description of the revitalization during WWII, published in Cramp Shipbuilding Company, 1940-1944 ].

Cramp Shipyard has a venerable history dating back to the year 1830, when it was founded by William Cramp. As the years went by, the yard grew until during the first World War it covered 59 acres and employed some 10,500 marine workers. In 1927, owing to lack of work and unfavorable conditions in the ship-building industry, the ninety-seven-year-old Company decided to give up the marine business, sell its tools and equipment, separate its non-marine departments and subsidiaries, and close its gates. Thirteen years later, in 1940, the present company, the Cramp Shipbuilding Company, was established with the approval of the Secretary of the Navy in order to undertake the reopening of the old Cramp Shipyard for the construction of urgently needed ships of war for the United States Navy. The reopening of the yard was accomplished with a minimum of delay as a result of the effort of the newly born company working in close co-operation with the Navy Department.

Accordingly, with the co-operation and financial assistance of the Navy Department, a program for reopening the historic shipyard was evolved and under-written by Harriman Ripley & Co., Incorporated, so as to permit it again to take its place among the foremost shipbuilding and ship repair yards of this country. The yard was reopened in October, 1940. After Pearl Harbor the facilities program, at the request of the Navy, was greatly enlarged with naval funds so as to include a concrete dry dock and repair base and facilities for submarine construction.

At the time of reopening, although the plant was in a rather dilapidated condition, there remained, in a fairly good state of preservation, two large concrete ship-ways and two small shipways, a large wet dock with servicing cranes, shipway cranes, a fabricating shop, a large office building, an outfitting building, and other useful structures. The real estate, with its excellent water front on the Delaware River, was of great value. In the adjacent Kensington district, one of the finest industrial sections in the country, there have always resided many workmen skilled in the arts of shipbuilding. Consequently, the shipyard was never faced with a housing problem.

At present, the yard, employing over 15,000 men and women, covers some 65 acres, not including leased storage space; and the former facilities have been replaced, enlarged, or rebuilt to such an extent that if the ghosts of William Cramp and his sons were to appear they would hardly recognize the old stamping ground. The planners of the new Cramp Shipbuilding Company reconstructed the plant with an eye to "streamlining" production. Old buildings poorly located were demolished, while new ones were added to suit the scheme. Arrangement was designed to approximate the "production line" system of construction. Although a ship cannot be moved during its construction like an automobile or a refrigerator, it is possible to apply "production line" methods to the movement of its parts as they go down from the storage yards to the ways. The present layout of the Cramp Yard was so carefully planned that it has become an extremely effective setup for building ships.

One may attain the idea of the "production line" scheme from a brief description of the yard. Richmond Street, along which the property extends for some 1,300 feet, is approximately parallel to the Delaware River; the buildings generally run parallel to both. The area occupied between the street and the water is about 60 acres. At the south end of the property, along Richmond Street, is a long two-story structure containing a receiving department, stores, a trade and a testing laboratory. Adjacent to this is a nine-story administration building. Here are located the drafting rooms, the Navy headquarters, and the main offices. North of this building are an entrance gate, a timekeeper's office, a reproduction department, a guard house, a rigging loft, and at the north corner, a large pipe shop. Between these buildings and the water front are the outside steel-storage racks, the main fabricating shop, and the pre-assembly platens. These three extensive areas reach practically from one end of the yard to the other. A crane system traverses the entire space, so that steel may be carried from the storage racks directly into the south end of the fabricating shop, formed and partially assembled, then carried by the same cranes northward to the pre-assembly platens, where it can be welded into structures as large as the overhead bridge cranes will carry. Thence the assemblies can be carried by bridge cranes down to the shipways and joined together into hulls. The bridge cranes are capable of carrying assemblies of approximately 75 tons directly from the platens down to the shipways without interference.

The efficiency of this method of handling material is considerably greater than that achieved in former days, for steel may thus be moved to any desired position while being assembled. In the old days, only small and minor pre-assembled sections were taken to the vessels on the ways.

Along the water front are located the new graving dock, a series of outfitting piers, modern concrete shipways capable of accommodating vessels from 650 to 700 feet long, and to the extreme north, the large wet basin. This basin is served by three hammerhead cranes. At the head of the wet basin are the electrical shop, the outside machine shop, the sheet metal shop, and the shipwright and carpenter shop. Also located in this vicinity are the paint shop and the out-fitting stores building.

A second fabricating shop, smaller than the main fabricating shop, is located between the shipways and the dry dock. Most of this shop is used for the assembly of large fabricated sections of submarines. The submarine program has become so extensive that it has been found necessary to devote special facilities to the construction of hull sections for these vessels alone. A forge shop is also located in the smaller fabricating shop. It is planned that this shop will eventually be used for other types of vessels.

On the other side of Richmond Street, on a triangular plot, stands the large building which houses the turret and machine shops. This structure alone covers more than 3 1/2 acres.

A network of railroad tracks connects the various buildings with the Pennsylvania and Reading lines.

In order that our nation may receive the support which it requires today, the shipyard is carrying on its honorable tradition by throwing the full weight of its efforts into the task of building up the Navy.

BEER

Kensington and Northern Liberties was home to many brewers including Christian Schmidt, Theodore Finkenauer, Frederick Feil, John Roehm, Joseph Rieger, William Heimgaertner, Albert Wolf, John Wagner and generations of Ortliebs. We will pass a few of the surviving brewing buildings, most near ruin. A rare survivor in decent shape is the “Emil Schaefer—Copper, Brass and Iron Works, Manufacturer of Brewers, Distillers and Sugar Refining Apparatus” at 1321-1312 North Randolph Street.

Yards Brewing purchased the former Weisbrod & Hess Brewery in May 2001 and started brewing beer in March 2002. Brewing capacity has grown from 2,500 barrels to 8,000 barrels in 2006. All brewing starts with 30 barrels; mixed into 60 barrel fermenters. Half the production is of Philadelphia Pale Ale, "a Pale Ale brewed with a Pilsner malt." Other beers brewed regularly include India Pale Ale, Extra Special Ale, Saison and three "Ales of the Revolution" brewed according to the historic recipes of three founding fathers: General Washington Porter, Thomas Jefferson Tavern Ale and Poor Richard's Tavern Spruce [Ben Franklin]. Yards uses Simcoe hops from the Yakima Valley region of Washington state and malts from the US and Germany. Yards sells direct to over 330 accounts in the Philadelphia area and this high local demand has restricted the availability elsewhere. Tastings will be offered.

Yards was started by John Bovit and Tom Kehoe in 1995 in Manayunk, moving eighteen months later Roxborough. In 1998. Bovit left and Kehoe (President) was joined by Nancy Barton (Secretary-Treasurer) and her husband Bill Barton (Vice President). Thirteen people are on the Yards staff including head brewer Josh Ervine, the "Parson of Fermentation" Dean Brown [a skilled brewer] and "The Enabler" Chris Morris [Sales Manager]. It was the Barton's who found this building, noticing the "Bottling Plant" sign after delivering beer to a local customer. The complex was then stuffed with used supermarket equipment—deli cases, carts, shelving, scales—offered for resale.

Yards brews on the second floor of the former W&H Bottling Plant and the gently sloping concrete floors and two original floor drains still serve their original purpose (large windows to the west offer a rooftop glimpse to a concentrated collection of Kensington mill buildings clustered near Coral and Front Streets). Bottling is done downstairs on a line requiring five pairs of hands. Kegging can be done by one. The Bartons have visited breweries in Europe and hosted Brew Masters at Yards to learn how to increase capacity within the building; they now estimate they can grow to between 20,000 and 40,000 barrels per year. The packaging and shipping room is on the first floor of the building to the north of the courtyard while the office and tasting room are above (often used by community groups as meeting space).

1 Samuel Needles, “ The Governor’s Mill, and the Globe Mills, Philadelphia,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 8, pp. 279-299, 377-390.

2 Werner von Bergen & Herbert R. Mauersberger, American Wool Handbook (Textile Book Publishers, NY, 1948), p. 5

3 For more information on the early textile industry in Philadelphia read chapter 7, “Manayunk, an overview” in Workshop of the World , (Oliver Evans Press, 1990).

4 Weaving, knitting, braiding, etc. were separate operations often done in separate establishments or “mills.”

5 John James MacFarlane, Textile Industries of Philadelphia (Philadelphia Commercial Museum, 1910).

6 Charles Childs, County Cloth, Paris, Ohio