PAUL WAGNER, former co-owner of H. RIEHL & SON, TEXTILE MACHINERY

As they approached the age of 80, Paul and Bill Wagner warned their customers that retirement was imminent and that final orders should be placed. In flowed the work to be fulfilled by the Wagner brothers and their five employees. Bill Wagner was ready to close five years earlier but he and Paul “felt a loyalty to their long term employees, like Amos, who was our best woodworker, he made the straight rack blocks, ran grooves in the shuttles and worked on the comber boards” [the comb-like device which directs the thread under a Jacquard, it replaces the harness frame on regular looms]. Paul and Bill closed shop and left in 2003 but Amos Tomlinson stayed on to work with the new owners of the building, custom woodworkers, Matt and Ian Pappajohn.

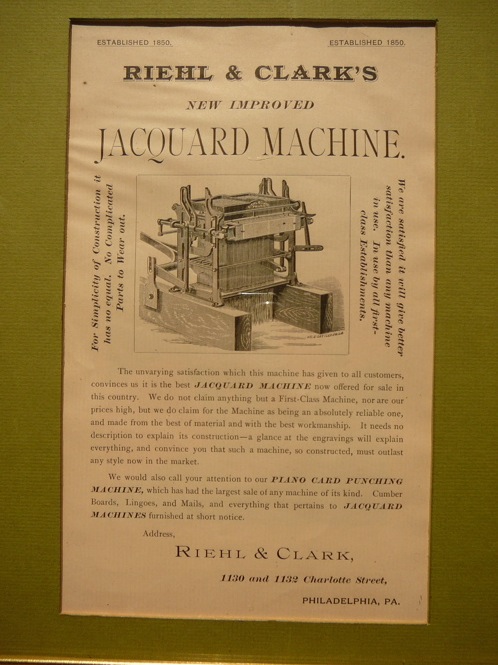

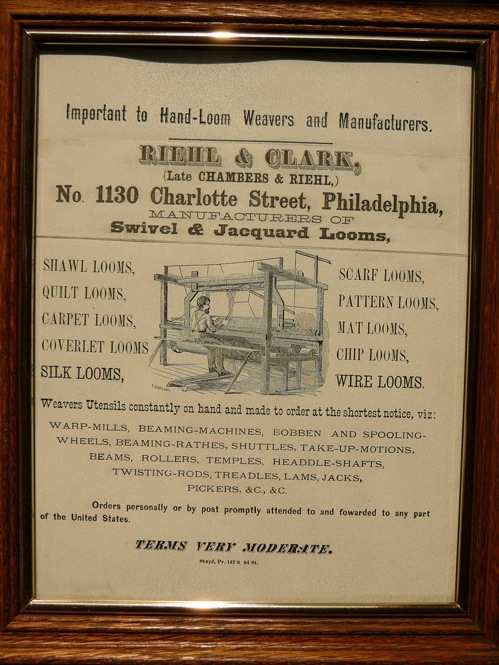

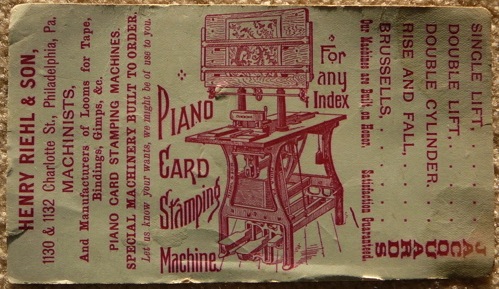

In 1946 “out of the service and with only a high school education and a year of college on Uncle Sam” Paul Wagner and his bothers Bill & Bob joined their father (Ferdinand) and uncle (Theodore) who operated H. Riehl & Son, a textile machinery firm with roots dating back to 1850. 7 Wagner spent that first year getting the building back into shape. “Each window required 32 pieces of glass and I reglazed over 700 of them. With that experience I should have qualified for the glaziers union.” Wagner thinks the three story building at 4355 Orchard Street was built for the Wallace Wilson Hosiery Company in 1907. 8

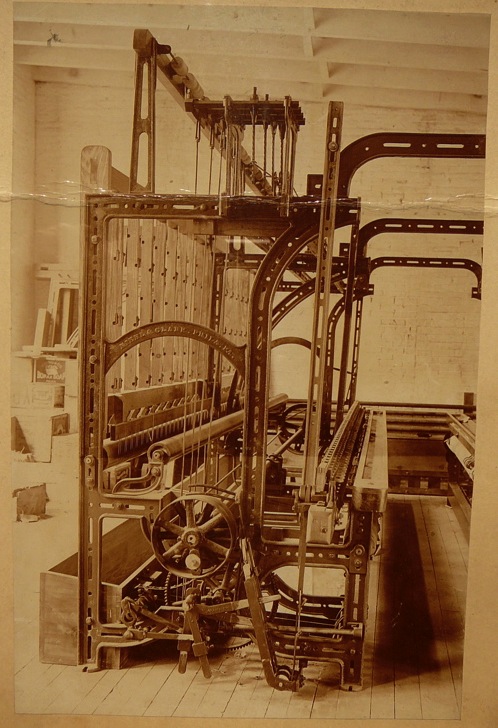

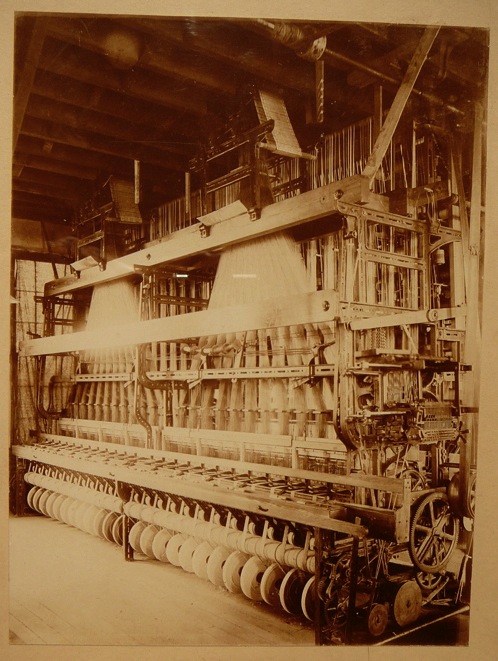

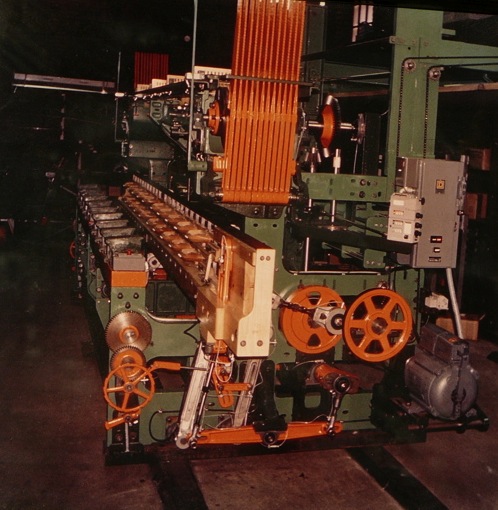

Solving problems appeals to Wagner. “I had no desire to earn a degree, only an interest to learn plain, twill, basket weave and countless other intricacies of weave formation.” Wagner spent three years of night school studying at the Philadelphia College of Textiles and Sciences then spent over fifty years maintaining and improving textile machinery. Wagner developed his practical skills in Riehl’s complete woodworking and machine shop. Here patterns were made in wood for the foundries to cast into brass, bronze, iron and aluminum to be assembled into ever more capable textile weaving equipment. During the 1950s Wagner improved narrow fabric looms with multiple shuttles. With increasing confidence, Wagner overcame the reservations of his father and uncle to introduce label looms in the 1960s. He laughs as he describes a loom he designed to make mop heads. Wagner perfected his skills on complex Dobbie Looms and Jacquards. 9 Wagner went on to earn a patent for “a special lifting motion, it used half the parts of, yet fit on, the competitors loom frame.” Then the faster needle looms took over “needing just an operator, not a weaver.”

Phoenix Trimming ordered thirty seven shuttle looms to weave seat belts. Narricott bought looms to weave seat belts and webbing “cargo slings” for the transportation industry. Bally Ribbon bought lots of shuttles and blocks. Bally specializes in engineered woven narrow fabrics, specialty broadcloth and woven structures for medical, military, safety, industrial, aerospace and commercial applications . Wagner says “Bally are superb weavers. They can weave fabric into a spiral, like a Slinky. Made from graphite or composites I suspect they are used for the nose cones on rockets.” In his final years, Riehl rebuilt about three quarters of the Jacquards for Langhorne Carpet, renowned for their exact reproductions for Independence Hall, Colonial Williamsburg, Winterthur and private clients.

When asked about his favorite memories of his final working years, Wagner says “two things: answering questions from and demonstrating weaving techniques to various students from Philadelphia University (formerly the Philadelphia College of Textiles and Sciences where Wagner spent three years at night school) and looms to weave the bifurcated tubes used for bypass surgery” (imagine a tubular sleeve that divides like the letter ‘Y’). Single tubes had been knitted before but this bifurcated tube was woven. When Bill Wagner had open heart surgery in 2000 this bifurcated tube was used, so he walks around with a product made by a machine that they helped to design and manufacture.

Riehl patterns.

On our tour, Paul Wagner and Amos Tomlinson will share their experience and stories with us and explain some of the over 1,000 patterns they carved (usually coated in red or black lacquer) to build their largest looms which sold for $32,000.

Their straight and circular shuttles will also be demonstrated; made from Dogwood and maple then impregnated with wax or clear shellac, these sold for $25-30 and were replaced “after having run round the clock for four years.”